Filter

Associated Lab

- Aso Lab (2) Apply Aso Lab filter

- Bock Lab (1) Apply Bock Lab filter

- Card Lab (1) Apply Card Lab filter

- Cardona Lab (1) Apply Cardona Lab filter

- Fetter Lab (4) Apply Fetter Lab filter

- Funke Lab (2) Apply Funke Lab filter

- Harris Lab (1) Apply Harris Lab filter

- Hess Lab (11) Apply Hess Lab filter

- Jayaraman Lab (2) Apply Jayaraman Lab filter

- Reiser Lab (1) Apply Reiser Lab filter

- Romani Lab (1) Apply Romani Lab filter

- Rubin Lab (8) Apply Rubin Lab filter

- Saalfeld Lab (3) Apply Saalfeld Lab filter

- Remove Scheffer Lab filter Scheffer Lab

- Sternson Lab (1) Apply Sternson Lab filter

- Turner Lab (1) Apply Turner Lab filter

Associated Project Team

Associated Support Team

Publication Date

- 2025 (2) Apply 2025 filter

- 2023 (2) Apply 2023 filter

- 2022 (1) Apply 2022 filter

- 2021 (2) Apply 2021 filter

- 2020 (1) Apply 2020 filter

- 2019 (2) Apply 2019 filter

- 2018 (4) Apply 2018 filter

- 2017 (4) Apply 2017 filter

- 2015 (2) Apply 2015 filter

- 2014 (7) Apply 2014 filter

- 2013 (3) Apply 2013 filter

- 2012 (3) Apply 2012 filter

- 2011 (2) Apply 2011 filter

- 2010 (3) Apply 2010 filter

38 Janelia Publications

Showing 1-10 of 38 resultsSynaptic circuits for identified behaviors in the Drosophila brain have typically been considered from either a developmental or functional perspective without reference to how the circuits might have been inherited from ancestral forms. For example, two candidate pathways for ON- and OFF-edge motion detection in the visual system act via circuits that use respectively either T4 or T5, two cell types of the fourth neuropil, or lobula plate (LOP), that exhibit narrow-field direction-selective responses and provide input to wide-field tangential neurons. T4 or T5 both have four subtypes that terminate one each in the four strata of the LOP. Representatives are reported in a wide range of Diptera, and both cell types exhibit various similarities in: (1) the morphology of their dendritic arbors; (2) their four morphological and functional subtypes; (3) their cholinergic profile in Drosophila; (4) their input from the pathways of L3 cells in the first neuropil, or lamina (LA), and by one of a pair of LA cells, L1 (to the T4 pathway) and L2 (to the T5 pathway); and (5) their innervation by a single, wide-field contralateral tangential neuron from the central brain. Progenitors of both also express the gene atonal early in their proliferation from the inner anlage of the developing optic lobe, being alone among many other cell type progeny to do so. Yet T4 receives input in the second neuropil, or medulla (ME), and T5 in the third neuropil or lobula (LO). Here we suggest that these two cell types were originally one, that their ancestral cell population duplicated and split to innervate separate ME and LO neuropils, and that a fiber crossing-the internal chiasma-arose between the two neuropils. The split most plausibly occurred, we suggest, with the formation of the LO as a new neuropil that formed when it separated from its ancestral neuropil to leave the ME, suggesting additionally that ME input neurons to T4 and T5 may also have had a common origin.

The neural circuits responsible for animal behavior remain largely unknown. We summarize new methods and present the circuitry of a large fraction of the brain of the fruit fly . Improved methods include new procedures to prepare, image, align, segment, find synapses in, and proofread such large data sets. We define cell types, refine computational compartments, and provide an exhaustive atlas of cell examples and types, many of them novel. We provide detailed circuits consisting of neurons and their chemical synapses for most of the central brain. We make the data public and simplify access, reducing the effort needed to answer circuit questions, and provide procedures linking the neurons defined by our analysis with genetic reagents. Biologically, we examine distributions of connection strengths, neural motifs on different scales, electrical consequences of compartmentalization, and evidence that maximizing packing density is an important criterion in the evolution of the fly's brain.

Understanding the structure and operation of any nervous system has been a subject of research for well over a century. A near-term opportunity in this quest is to understand the brain of a model species, the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. This is an enticing target given its relatively small size (roughly 200,000 neurons), coupled with the behavioral richness that this brain supports, and the wide variety of techniques now available to study both brain and behavior. It is clear that within a few years we will possess a connectome for D. melanogaster: an electron-microscopy-level description of all neurons and their chemical synaptic connections. Given what we will soon have, what we already know and the research that is currently underway, what more do we need to know to enable us to understand the fly's brain? Here, we itemize the data we will need to obtain, collate and organize in order to build an integrated model of the brain of D. melanogaster.

Understanding memory formation, storage and retrieval requires knowledge of the underlying neuronal circuits. In Drosophila, the mushroom body (MB) is the major site of associative learning. We reconstructed the morphologies and synaptic connections of all 983 neurons within the three functional units, or compartments, that compose the adult MB’s α lobe, using a dataset of isotropic 8-nm voxels collected by focused ion-beam milling scanning electron microscopy. We found that Kenyon cells (KCs), whose sparse activity encodes sensory information, each make multiple en passant synapses to MB output neurons (MBONs) in each compartment. Some MBONs have inputs from all KCs, while others differentially sample sensory modalities. Only six percent of KC>MBON synapses receive a direct synapse from a dopaminergic neuron (DAN). We identified two unanticipated classes of synapses, KC>DAN and DAN>MBON. DAN activation produces a slow depolarization of the MBON in these DAN>MBON synapses and can weaken memory recall.

Animal behavior is principally expressed through neural control of muscles. Therefore understanding how the brain controls behavior requires mapping neuronal circuits all the way to motor neurons. We have previously established technology to collect large-volume electron microscopy data sets of neural tissue and fully reconstruct the morphology of the neurons and their chemical synaptic connections throughout the volume. Using these tools we generated a dense wiring diagram, or connectome, for a large portion of the Drosophila central brain. However, in most animals, including the fly, the majority of motor neurons are located outside the brain in a neural center closer to the body, i.e. the mammalian spinal cord or insect ventral nerve cord (VNC). In this paper, we extend our effort to map full neural circuits for behavior by generating a connectome of the VNC of a male fly.

This paper proposes a novel agglomerative framework for Electron Microscopy (EM) image (or volume) segmentation. For the overall segmentation methodology, we propose a context-aware algorithm that clusters the over-segmented regions of different sub-classes (representing different biological entities) in different stages. Furthermore, a delayed scheme for agglomerative clustering, which postpones the merge of newly formed bodies, is also proposed to generate a more confident boundary prediction. We report significant improvements in both segmentation accuracy and speed attained by the proposed approaches over existing standard methods on both 2D and 3D datasets.

Synaptic connectivity and molecular composition provide a blueprint for information processing in neural circuits. Detailed structural analysis of neural circuits requires nanometer resolution, which can be obtained with serial-section electron microscopy. However, this technique remains challenging for reconstructing molecularly defined synapses. We used a genetically encoded synaptic marker for electron microscopy (GESEM) based on intra-vesicular generation of electron-dense labeling in axonal boutons. This approach allowed the identification of synapses from Cre recombinase-expressing or GAL4-expressing neurons in the mouse and fly with excellent preservation of ultrastructure. We applied this tool to visualize long-range connectivity of AGRP and POMC neurons in the mouse, two molecularly defined hypothalamic populations that are important for feeding behavior. Combining selective ultrastructural reconstruction of neuropil with functional and viral circuit mapping, we characterized some basic features of circuit organization for axon projections of these cell types. Our findings demonstrate that GESEM labeling enables long-range connectomics with molecularly defined cell types.

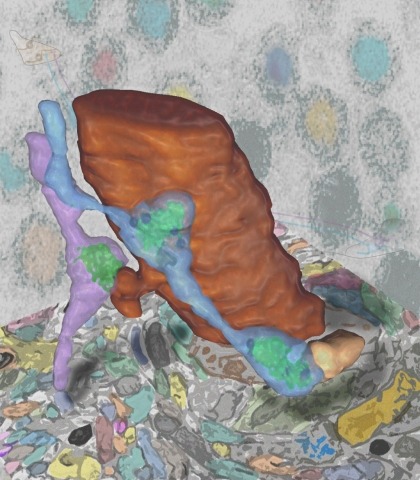

Using FIB-SEM we report the entire synaptic connectome of glomerulus VA1v of the right antennal lobe in . Within the glomerulus we densely reconstructed all neurons, including hitherto elusive local interneurons. The -positive, sexually dimorphic VA1v included >11,140 presynaptic sites with ~38,050 postsynaptic dendrites. These connected input olfactory receptor neurons (ORNs, 51 ipsilateral, 56 contralateral), output projection neurons (18 PNs), and local interneurons (56 of >150 previously reported LNs). ORNs are predominantly presynaptic and PNs predominantly postsynaptic; newly reported LN circuits are largely an equal mixture and confer extensive synaptic reciprocity, except the newly reported LN2V with input from ORNs and outputs mostly to monoglomerular PNs, however. PNs were more numerous than previously reported from genetic screens, suggesting that the latter failed to reach saturation. We report a matrix of 192 bodies each having 50 connections; these form 88% of the glomerulus' pre/postsynaptic sites.

Animal behaviour arises from computations in neuronal circuits, but our understanding of these computations has been frustrated by the lack of detailed synaptic connection maps, or connectomes. For example, despite intensive investigations over half a century, the neuronal implementation of local motion detection in the insect visual system remains elusive. Here we develop a semi-automated pipeline using electron microscopy to reconstruct a connectome, containing 379 neurons and 8,637 chemical synaptic contacts, within the Drosophila optic medulla. By matching reconstructed neurons to examples from light microscopy, we assigned neurons to cell types and assembled a connectome of the repeating module of the medulla. Within this module, we identified cell types constituting a motion detection circuit, and showed that the connections onto individual motion-sensitive neurons in this circuit were consistent with their direction selectivity. Our results identify cellular targets for future functional investigations, and demonstrate that connectomes can provide key insights into neuronal computations.

New reconstruction techniques are generating connectomes of unprecedented size. These must be analyzed to generate human comprehensible results. The analyses being used fall into three general categories. The first is interactive tools used during reconstruction, to help guide the effort, look for possible errors, identify potential cell classes, and answer other preliminary questions. The second type of analysis is support for formal documents such as papers and theses. Scientific norms here require that the data be archived and accessible, and the analysis reproducible. In contrast to some other "omic" fields such as genomics, where a few specific analyses dominate usage, connectomics is rapidly evolving and the analyses used are often specific to the connectome being analyzed. These analyses are typically performed in a variety of conventional programming language, such as Matlab, R, Python, or C++, and read the connectomic data either from a file or through database queries, neither of which are standardized. In the short term we see no alternative to the use of specific analyses, so the best that can be done is to publish the analysis code, and the interface by which it reads connectomic data. A similar situation exists for archiving connectome data. Each group independently makes their data available, but there is no standardized format and long-term accessibility is neither enforced nor funded. In the long term, as connectomics becomes more common, a natural evolution would be a central facility for storing and querying connectomic data, playing a role similar to the National Center for Biotechnology Information for genomes. The final form of analysis is the import of connectome data into downstream tools such as neural simulation or machine learning. In this process, there are two main problems that need to be addressed. First, the reconstructed circuits contain huge amounts of detail, which must be intelligently reduced to a form the downstream tools can use. Second, much of the data needed for these downstream operations must be obtained by other methods (such as genetic or optical) and must be merged with the extracted connectome.