Filter

Associated Lab

- Aguilera Castrejon Lab (2) Apply Aguilera Castrejon Lab filter

- Ahrens Lab (58) Apply Ahrens Lab filter

- Aso Lab (42) Apply Aso Lab filter

- Baker Lab (19) Apply Baker Lab filter

- Betzig Lab (103) Apply Betzig Lab filter

- Beyene Lab (10) Apply Beyene Lab filter

- Bock Lab (14) Apply Bock Lab filter

- Branson Lab (51) Apply Branson Lab filter

- Card Lab (37) Apply Card Lab filter

- Cardona Lab (45) Apply Cardona Lab filter

- Chklovskii Lab (10) Apply Chklovskii Lab filter

- Clapham Lab (14) Apply Clapham Lab filter

- Cui Lab (19) Apply Cui Lab filter

- Darshan Lab (8) Apply Darshan Lab filter

- Dennis Lab (1) Apply Dennis Lab filter

- Dickson Lab (32) Apply Dickson Lab filter

- Druckmann Lab (21) Apply Druckmann Lab filter

- Dudman Lab (41) Apply Dudman Lab filter

- Eddy/Rivas Lab (30) Apply Eddy/Rivas Lab filter

- Egnor Lab (4) Apply Egnor Lab filter

- Espinosa Medina Lab (18) Apply Espinosa Medina Lab filter

- Feliciano Lab (10) Apply Feliciano Lab filter

- Fetter Lab (31) Apply Fetter Lab filter

- FIB-SEM Technology (1) Apply FIB-SEM Technology filter

- Fitzgerald Lab (16) Apply Fitzgerald Lab filter

- Freeman Lab (15) Apply Freeman Lab filter

- Funke Lab (42) Apply Funke Lab filter

- Gonen Lab (59) Apply Gonen Lab filter

- Grigorieff Lab (34) Apply Grigorieff Lab filter

- Harris Lab (55) Apply Harris Lab filter

- Heberlein Lab (13) Apply Heberlein Lab filter

- Hermundstad Lab (26) Apply Hermundstad Lab filter

- Hess Lab (76) Apply Hess Lab filter

- Ilanges Lab (3) Apply Ilanges Lab filter

- Jayaraman Lab (44) Apply Jayaraman Lab filter

- Ji Lab (33) Apply Ji Lab filter

- Johnson Lab (1) Apply Johnson Lab filter

- Karpova Lab (13) Apply Karpova Lab filter

- Keleman Lab (8) Apply Keleman Lab filter

- Keller Lab (61) Apply Keller Lab filter

- Koay Lab (3) Apply Koay Lab filter

- Lavis Lab (144) Apply Lavis Lab filter

- Lee (Albert) Lab (29) Apply Lee (Albert) Lab filter

- Leonardo Lab (19) Apply Leonardo Lab filter

- Li Lab (6) Apply Li Lab filter

- Lippincott-Schwartz Lab (107) Apply Lippincott-Schwartz Lab filter

- Liu (Yin) Lab (2) Apply Liu (Yin) Lab filter

- Liu (Zhe) Lab (59) Apply Liu (Zhe) Lab filter

- Looger Lab (137) Apply Looger Lab filter

- Magee Lab (31) Apply Magee Lab filter

- Menon Lab (12) Apply Menon Lab filter

- Murphy Lab (6) Apply Murphy Lab filter

- O'Shea Lab (6) Apply O'Shea Lab filter

- Otopalik Lab (1) Apply Otopalik Lab filter

- Pachitariu Lab (39) Apply Pachitariu Lab filter

- Pastalkova Lab (5) Apply Pastalkova Lab filter

- Pavlopoulos Lab (7) Apply Pavlopoulos Lab filter

- Pedram Lab (4) Apply Pedram Lab filter

- Podgorski Lab (16) Apply Podgorski Lab filter

- Reiser Lab (49) Apply Reiser Lab filter

- Riddiford Lab (20) Apply Riddiford Lab filter

- Romani Lab (39) Apply Romani Lab filter

- Rubin Lab (110) Apply Rubin Lab filter

- Saalfeld Lab (47) Apply Saalfeld Lab filter

- Satou Lab (1) Apply Satou Lab filter

- Scheffer Lab (38) Apply Scheffer Lab filter

- Schreiter Lab (52) Apply Schreiter Lab filter

- Sgro Lab (2) Apply Sgro Lab filter

- Shroff Lab (31) Apply Shroff Lab filter

- Simpson Lab (18) Apply Simpson Lab filter

- Singer Lab (37) Apply Singer Lab filter

- Spruston Lab (61) Apply Spruston Lab filter

- Stern Lab (75) Apply Stern Lab filter

- Sternson Lab (47) Apply Sternson Lab filter

- Stringer Lab (36) Apply Stringer Lab filter

- Svoboda Lab (132) Apply Svoboda Lab filter

- Tebo Lab (11) Apply Tebo Lab filter

- Tervo Lab (9) Apply Tervo Lab filter

- Tillberg Lab (18) Apply Tillberg Lab filter

- Tjian Lab (17) Apply Tjian Lab filter

- Truman Lab (58) Apply Truman Lab filter

- Turaga Lab (41) Apply Turaga Lab filter

- Turner Lab (27) Apply Turner Lab filter

- Vale Lab (8) Apply Vale Lab filter

- Voigts Lab (4) Apply Voigts Lab filter

- Wang (Meng) Lab (27) Apply Wang (Meng) Lab filter

- Wang (Shaohe) Lab (6) Apply Wang (Shaohe) Lab filter

- Wong-Campos Lab (1) Apply Wong-Campos Lab filter

- Wu Lab (8) Apply Wu Lab filter

- Zlatic Lab (26) Apply Zlatic Lab filter

- Zuker Lab (5) Apply Zuker Lab filter

Associated Project Team

- CellMap (12) Apply CellMap filter

- COSEM (3) Apply COSEM filter

- FIB-SEM Technology (5) Apply FIB-SEM Technology filter

- Fly Descending Interneuron (12) Apply Fly Descending Interneuron filter

- Fly Functional Connectome (14) Apply Fly Functional Connectome filter

- Fly Olympiad (5) Apply Fly Olympiad filter

- FlyEM (56) Apply FlyEM filter

- FlyLight (50) Apply FlyLight filter

- GENIE (47) Apply GENIE filter

- Integrative Imaging (9) Apply Integrative Imaging filter

- Larval Olympiad (2) Apply Larval Olympiad filter

- MouseLight (18) Apply MouseLight filter

- NeuroSeq (1) Apply NeuroSeq filter

- ThalamoSeq (1) Apply ThalamoSeq filter

- Tool Translation Team (T3) (29) Apply Tool Translation Team (T3) filter

- Transcription Imaging (45) Apply Transcription Imaging filter

Associated Support Team

- Project Pipeline Support (5) Apply Project Pipeline Support filter

- Anatomy and Histology (18) Apply Anatomy and Histology filter

- Cryo-Electron Microscopy (41) Apply Cryo-Electron Microscopy filter

- Electron Microscopy (18) Apply Electron Microscopy filter

- Gene Targeting and Transgenics (11) Apply Gene Targeting and Transgenics filter

- High Performance Computing (7) Apply High Performance Computing filter

- Integrative Imaging (18) Apply Integrative Imaging filter

- Invertebrate Shared Resource (40) Apply Invertebrate Shared Resource filter

- Janelia Experimental Technology (37) Apply Janelia Experimental Technology filter

- Management Team (1) Apply Management Team filter

- Mass Spectrometry (1) Apply Mass Spectrometry filter

- Molecular Genomics (15) Apply Molecular Genomics filter

- Primary & iPS Cell Culture (14) Apply Primary & iPS Cell Culture filter

- Project Technical Resources (53) Apply Project Technical Resources filter

- Quantitative Genomics (20) Apply Quantitative Genomics filter

- Scientific Computing (100) Apply Scientific Computing filter

- Viral Tools (14) Apply Viral Tools filter

- Vivarium (7) Apply Vivarium filter

Publication Date

- 2026 (17) Apply 2026 filter

- 2025 (225) Apply 2025 filter

- 2024 (211) Apply 2024 filter

- 2023 (157) Apply 2023 filter

- 2022 (166) Apply 2022 filter

- 2021 (175) Apply 2021 filter

- 2020 (177) Apply 2020 filter

- 2019 (177) Apply 2019 filter

- 2018 (206) Apply 2018 filter

- 2017 (186) Apply 2017 filter

- 2016 (191) Apply 2016 filter

- 2015 (195) Apply 2015 filter

- 2014 (190) Apply 2014 filter

- 2013 (136) Apply 2013 filter

- 2012 (112) Apply 2012 filter

- 2011 (98) Apply 2011 filter

- 2010 (61) Apply 2010 filter

- 2009 (56) Apply 2009 filter

- 2008 (40) Apply 2008 filter

- 2007 (21) Apply 2007 filter

- 2006 (3) Apply 2006 filter

2800 Janelia Publications

Showing 1501-1510 of 2800 resultsThe measurement of ion concentrations and fluxes inside living cells is key to understanding cellular physiology. Fluorescent indicators that can infiltrate and provide intel on the cellular environment are critical tools for biological research. Developing these molecular informants began with the seminal work of Racker and colleagues ( (1979) 18, 2210), who demonstrated the passive loading of fluorescein in living cells to measure changes in intracellular pH. This work continues, employing a mix of old and new tradecraft to create innovative agents for monitoring ions inside living systems.

Stoichiometric labeling of endogenous synaptic proteins for high-contrast live-cell imaging in brain tissue remains challenging. Here, we describe a conditional mouse genetic strategy termed endogenous labeling via exon duplication (ENABLED), which can be used to fluorescently label endogenous proteins with near ideal properties in all neurons, a sparse subset of neurons, or specific neuronal subtypes. We used this method to label the postsynaptic density protein PSD-95 with mVenus without overexpression side effects. We demonstrated that mVenus-tagged PSD-95 is functionally equivalent to wild-type PSD-95 and that PSD-95 is present in nearly all dendritic spines in CA1 neurons. Within spines, while PSD-95 exhibited low mobility under basal conditions, its levels could be regulated by chronic changes in neuronal activity. Notably, labeled PSD-95 also allowed us to visualize and unambiguously examine otherwise-unidentifiable excitatory shaft synapses in aspiny neurons, such as parvalbumin-positive interneurons and dopaminergic neurons. Our results demonstrate that the ENABLED strategy provides a valuable new approach to study the dynamics of endogenous synaptic proteins in vivo.

In vivo imaging applications typically require carefully balancing conflicting parameters. Often it is necessary to achieve high imaging speed, low photo-bleaching, and photo-toxicity, good three-dimensional resolution, high signal-to-noise ratio, and excellent physical coverage at the same time. Light-sheet microscopy provides good performance in all of these categories, and is thus emerging as a particularly powerful live imaging method for the life sciences. We see an outstanding potential for applying light-sheet microscopy to the study of development and function of the early nervous system in vertebrates and higher invertebrates. Here, we review state-of-the-art approaches to live imaging of early development, and show how the unique capabilities of light-sheet microscopy can further advance our understanding of the development and function of the nervous system. We discuss key considerations in the design of light-sheet microscopy experiments, including sample preparation and fluorescent marker strategies, and provide an outlook for future directions in the field.

All multicellular systems produce and dynamically regulate extracellular matrices (ECMs) that play essential roles in both biochemical and mechanical signaling. Though the spatial arrangement of these extracellular assemblies is critical to their biological functions, visualization of ECM structure is challenging, in part because the biomolecules that compose the ECM are difficult to fluorescently label individually and collectively. Here, we present a cell-impermeable small-molecule fluorophore, termed Rhobo6, that turns on and red shifts upon reversible binding to glycans. Given that most ECM components are densely glycosylated, the dye enables wash-free visualization of ECM, in systems ranging from in vitro substrates to in vivo mouse mammary tumors. Relative to existing techniques, Rhobo6 provides a broad substrate profile, superior tissue penetration, non-perturbative labeling, and negligible photobleaching. This work establishes a straightforward method for imaging the distribution of ECM in live tissues and organisms, lowering barriers for investigation of extracellular biology.

At the time of this writing, searching Google Scholar for 'light-sheet microscopy' returns almost 8500 results; over three-quarters of which were published in the last 5 years alone. Searching for other advanced imaging methods in the last 5 years yields similar results: 'super-resolution microscopy' (>16 000), 'single-molecule imaging' (almost 10 000), SPIM (Single Plane Illumination Microscopy, 5000), and 'lattice light-sheet' (1300). The explosion of new imaging methods has also produced a dizzying menagerie of acronyms, with over 100 different species of 'light-sheet' alone, from SPIM to UM (Ultra microscopy) to SiMView (Simultaneous MultiView) to iSPIM (inclined SPIM, not to be confused with iSPIM, inverted SPIM). How then is the average biologist, without an advanced degree in physics, optics, or computer science supposed to make heads or tails of which method is best suited for their needs? Let us also not forget the plight of the optical physicist, who at best might need help with obtaining healthy samples and keeping them that way, or at worst may not realize the impact their newest technique could have for biologists. This review will not attempt to solve all these problems, but instead highlight some of the most recent, successful mergers between biology and advanced imaging technologies, as well as hopefully provide some guidance for anyone interested in journeying into the world of live-cell imaging.

The proliferation of microscopy methods for live-cell imaging offers many new possibilities for users but can also be challenging to navigate. The prevailing challenge in live-cell fluorescence microscopy is capturing intra-cellular dynamics while preserving cell viability. Computational methods can help to address this challenge and are now shifting the boundaries of what is possible to capture in living systems. In this Review, we discuss these computational methods focusing on artificial intelligence-based approaches that can be layered on top of commonly used existing microscopies as well as hybrid methods that integrate computation and microscope hardware. We specifically discuss how computational approaches can improve the signal-to-noise ratio, spatial resolution, temporal resolution and multi-colour capacity of live-cell imaging.

We demonstrate live-cell super-resolution imaging using photoactivated localization microscopy (PALM). The use of photon-tolerant cell lines in combination with the high resolution and molecular sensitivity of PALM permitted us to investigate the nanoscale dynamics within individual adhesion complexes (ACs) in living cells under physiological conditions for as long as 25 min, with half of the time spent collecting the PALM images at spatial resolutions down to approximately 60 nm and frame rates as short as 25 s. We visualized the formation of ACs and measured the fractional gain and loss of individual paxillin molecules as each AC evolved. By allowing observation of a wide variety of nanoscale dynamics, live-cell PALM provides insights into molecular assembly during the initiation, maturation and dissolution of cellular processes.

Commentary: The first example of true live cell and time lapse imaging by localization microscopy (as opposed to particle tracking), this paper uses the Nyquist criterion to establish a necessary condition for true spatial resolution based on the density of localized molecules – a condition often unmet in claims elsewhere in the superresolution literature.

By any method, higher spatiotemporal resolution requires increasing light exposure at the specimen, making noninvasive imaging increasingly difficult. Here, simultaneous differential interference contrast imaging is used to establish that cells behave physiologically before, during, and after PALM imaging. Similar controls are lacking from many supposed “live cell” superresolution demonstrations.

The H2A.Z histone variant, a genome-wide hallmark of permissive chromatin, is enriched near transcription start sites in all eukaryotes. H2A.Z is deposited by the SWR1 chromatin remodeler and evicted by unclear mechanisms. We tracked H2A.Z in living yeast at single-molecule resolution, and found that H2A.Z eviction is dependent on RNA Polymerase II (Pol II) and the Kin28/Cdk7 kinase, which phosphorylates Serine 5 of heptapeptide repeats on the carboxy-terminal domain of the largest Pol II subunit Rpb1. These findings link H2A.Z eviction to transcription initiation, promoter escape and early elongation activities of Pol II. Because passage of Pol II through +1 nucleosomes genome-wide would obligate H2A.Z turnover, we propose that global transcription at yeast promoters is responsible for eviction of H2A.Z. Such usage of yeast Pol II suggests a general mechanism coupling eukaryotic transcription to erasure of the H2A.Z epigenetic signal.

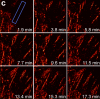

Stereocilia are F-actin-based cylindrical protrusions on the apical surface of inner ear hair cells that function as biological mechanosensors of sound and acceleration. During stereocilia development, specific unconventional myosins transport proteins and phospholipids as cargo and mediate elongation, differentiation and acquisition of the mechanoelectrical transduction (MET). How unconventional myosins localize themselves and cargo in stereocilia using energy from ATP hydrolysis is only partially understood. Here, we developed STELLA-SPIM microscopy to visualize movement of single myosin molecules in live hair cell stereocilia. STELLA-SPIM demonstrated that MYO7A, a component of MET machinery, shows processive movement toward stereocilia tips when chemically dimerized or constitutively activated by missense mutations disabling tail-mediated autoinhibition. Conversely, MYO7A shows step-wise but not processive movement in stereocilia when its tail is tethered to the plasma membrane or F-actin in the presence of MYO7A interacting partners. We posit that MYO7A dimerizes and moves processively in stereocilia when unleashed from autoinhibition.