Filter

Associated Lab

- Aguilera Castrejon Lab (17) Apply Aguilera Castrejon Lab filter

- Ahrens Lab (66) Apply Ahrens Lab filter

- Aso Lab (40) Apply Aso Lab filter

- Baker Lab (38) Apply Baker Lab filter

- Betzig Lab (113) Apply Betzig Lab filter

- Beyene Lab (14) Apply Beyene Lab filter

- Bock Lab (17) Apply Bock Lab filter

- Branson Lab (54) Apply Branson Lab filter

- Card Lab (43) Apply Card Lab filter

- Cardona Lab (64) Apply Cardona Lab filter

- Chklovskii Lab (13) Apply Chklovskii Lab filter

- Clapham Lab (15) Apply Clapham Lab filter

- Cui Lab (19) Apply Cui Lab filter

- Darshan Lab (12) Apply Darshan Lab filter

- Dennis Lab (1) Apply Dennis Lab filter

- Dickson Lab (46) Apply Dickson Lab filter

- Druckmann Lab (25) Apply Druckmann Lab filter

- Dudman Lab (50) Apply Dudman Lab filter

- Eddy/Rivas Lab (30) Apply Eddy/Rivas Lab filter

- Egnor Lab (11) Apply Egnor Lab filter

- Espinosa Medina Lab (19) Apply Espinosa Medina Lab filter

- Feliciano Lab (8) Apply Feliciano Lab filter

- Fetter Lab (41) Apply Fetter Lab filter

- FIB-SEM Technology (1) Apply FIB-SEM Technology filter

- Fitzgerald Lab (29) Apply Fitzgerald Lab filter

- Freeman Lab (15) Apply Freeman Lab filter

- Funke Lab (39) Apply Funke Lab filter

- Gonen Lab (91) Apply Gonen Lab filter

- Grigorieff Lab (62) Apply Grigorieff Lab filter

- Harris Lab (63) Apply Harris Lab filter

- Heberlein Lab (94) Apply Heberlein Lab filter

- Hermundstad Lab (28) Apply Hermundstad Lab filter

- Hess Lab (77) Apply Hess Lab filter

- Ilanges Lab (2) Apply Ilanges Lab filter

- Jayaraman Lab (46) Apply Jayaraman Lab filter

- Ji Lab (33) Apply Ji Lab filter

- Johnson Lab (6) Apply Johnson Lab filter

- Kainmueller Lab (19) Apply Kainmueller Lab filter

- Karpova Lab (14) Apply Karpova Lab filter

- Keleman Lab (13) Apply Keleman Lab filter

- Keller Lab (76) Apply Keller Lab filter

- Koay Lab (18) Apply Koay Lab filter

- Lavis Lab (151) Apply Lavis Lab filter

- Lee (Albert) Lab (34) Apply Lee (Albert) Lab filter

- Leonardo Lab (23) Apply Leonardo Lab filter

- Li Lab (28) Apply Li Lab filter

- Lippincott-Schwartz Lab (172) Apply Lippincott-Schwartz Lab filter

- Liu (Yin) Lab (7) Apply Liu (Yin) Lab filter

- Liu (Zhe) Lab (64) Apply Liu (Zhe) Lab filter

- Looger Lab (138) Apply Looger Lab filter

- Magee Lab (49) Apply Magee Lab filter

- Menon Lab (18) Apply Menon Lab filter

- Murphy Lab (13) Apply Murphy Lab filter

- O'Shea Lab (7) Apply O'Shea Lab filter

- Otopalik Lab (13) Apply Otopalik Lab filter

- Pachitariu Lab (48) Apply Pachitariu Lab filter

- Pastalkova Lab (18) Apply Pastalkova Lab filter

- Pavlopoulos Lab (19) Apply Pavlopoulos Lab filter

- Pedram Lab (15) Apply Pedram Lab filter

- Podgorski Lab (16) Apply Podgorski Lab filter

- Reiser Lab (51) Apply Reiser Lab filter

- Riddiford Lab (44) Apply Riddiford Lab filter

- Romani Lab (43) Apply Romani Lab filter

- Rubin Lab (145) Apply Rubin Lab filter

- Saalfeld Lab (63) Apply Saalfeld Lab filter

- Satou Lab (16) Apply Satou Lab filter

- Scheffer Lab (36) Apply Scheffer Lab filter

- Schreiter Lab (68) Apply Schreiter Lab filter

- Sgro Lab (21) Apply Sgro Lab filter

- Shroff Lab (31) Apply Shroff Lab filter

- Simpson Lab (23) Apply Simpson Lab filter

- Singer Lab (80) Apply Singer Lab filter

- Spruston Lab (94) Apply Spruston Lab filter

- Stern Lab (156) Apply Stern Lab filter

- Sternson Lab (54) Apply Sternson Lab filter

- Stringer Lab (36) Apply Stringer Lab filter

- Svoboda Lab (135) Apply Svoboda Lab filter

- Tebo Lab (33) Apply Tebo Lab filter

- Tervo Lab (9) Apply Tervo Lab filter

- Tillberg Lab (21) Apply Tillberg Lab filter

- Tjian Lab (64) Apply Tjian Lab filter

- Truman Lab (88) Apply Truman Lab filter

- Turaga Lab (52) Apply Turaga Lab filter

- Turner Lab (39) Apply Turner Lab filter

- Vale Lab (8) Apply Vale Lab filter

- Voigts Lab (3) Apply Voigts Lab filter

- Wang (Meng) Lab (22) Apply Wang (Meng) Lab filter

- Wang (Shaohe) Lab (25) Apply Wang (Shaohe) Lab filter

- Wu Lab (9) Apply Wu Lab filter

- Zlatic Lab (28) Apply Zlatic Lab filter

- Zuker Lab (25) Apply Zuker Lab filter

Associated Project Team

- CellMap (12) Apply CellMap filter

- COSEM (3) Apply COSEM filter

- FIB-SEM Technology (3) Apply FIB-SEM Technology filter

- Fly Descending Interneuron (11) Apply Fly Descending Interneuron filter

- Fly Functional Connectome (14) Apply Fly Functional Connectome filter

- Fly Olympiad (5) Apply Fly Olympiad filter

- FlyEM (54) Apply FlyEM filter

- FlyLight (49) Apply FlyLight filter

- GENIE (47) Apply GENIE filter

- Integrative Imaging (6) Apply Integrative Imaging filter

- Larval Olympiad (2) Apply Larval Olympiad filter

- MouseLight (18) Apply MouseLight filter

- NeuroSeq (1) Apply NeuroSeq filter

- ThalamoSeq (1) Apply ThalamoSeq filter

- Tool Translation Team (T3) (27) Apply Tool Translation Team (T3) filter

- Transcription Imaging (49) Apply Transcription Imaging filter

Publication Date

- 2025 (160) Apply 2025 filter

- 2024 (214) Apply 2024 filter

- 2023 (159) Apply 2023 filter

- 2022 (192) Apply 2022 filter

- 2021 (194) Apply 2021 filter

- 2020 (196) Apply 2020 filter

- 2019 (202) Apply 2019 filter

- 2018 (232) Apply 2018 filter

- 2017 (217) Apply 2017 filter

- 2016 (209) Apply 2016 filter

- 2015 (252) Apply 2015 filter

- 2014 (236) Apply 2014 filter

- 2013 (194) Apply 2013 filter

- 2012 (190) Apply 2012 filter

- 2011 (190) Apply 2011 filter

- 2010 (161) Apply 2010 filter

- 2009 (158) Apply 2009 filter

- 2008 (140) Apply 2008 filter

- 2007 (106) Apply 2007 filter

- 2006 (92) Apply 2006 filter

- 2005 (67) Apply 2005 filter

- 2004 (57) Apply 2004 filter

- 2003 (58) Apply 2003 filter

- 2002 (39) Apply 2002 filter

- 2001 (28) Apply 2001 filter

- 2000 (29) Apply 2000 filter

- 1999 (14) Apply 1999 filter

- 1998 (18) Apply 1998 filter

- 1997 (16) Apply 1997 filter

- 1996 (10) Apply 1996 filter

- 1995 (18) Apply 1995 filter

- 1994 (12) Apply 1994 filter

- 1993 (10) Apply 1993 filter

- 1992 (6) Apply 1992 filter

- 1991 (11) Apply 1991 filter

- 1990 (11) Apply 1990 filter

- 1989 (6) Apply 1989 filter

- 1988 (1) Apply 1988 filter

- 1987 (7) Apply 1987 filter

- 1986 (4) Apply 1986 filter

- 1985 (5) Apply 1985 filter

- 1984 (2) Apply 1984 filter

- 1983 (2) Apply 1983 filter

- 1982 (3) Apply 1982 filter

- 1981 (3) Apply 1981 filter

- 1980 (1) Apply 1980 filter

- 1979 (1) Apply 1979 filter

- 1976 (2) Apply 1976 filter

- 1973 (1) Apply 1973 filter

- 1970 (1) Apply 1970 filter

- 1967 (1) Apply 1967 filter

Type of Publication

4138 Publications

Showing 3601-3610 of 4138 resultsEstrogen promotes growth of estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) breast tumors. However, epidemiological studies examining the prognostic characteristics of breast cancer in postmenopausal women receiving hormone replacement therapy reveal a significant decrease in tumor dissemination, suggesting that estrogen has potential protective effects against cancer cell invasion. Here, we show that estrogen suppresses invasion of ER+ breast cancer cells by increasing transcription of the Ena/VASP protein, EVL, which promotes the generation of suppressive cortical actin bundles that inhibit motility dynamics, and is crucial for the ER-mediated suppression of invasion in vitro and in vivo. Interestingly, despite its benefits in suppressing tumor growth, anti-estrogenic endocrine therapy decreases EVL expression and increases local invasion in patients. Our results highlight the dichotomous effects of estrogen on tumor progression and suggest that, in contrast to its established role in promoting growth of ER+ tumors, estrogen has a significant role in suppressing invasion through actin cytoskeletal remodeling.

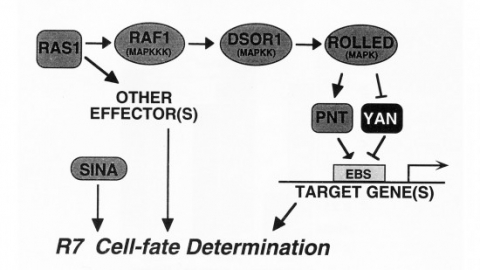

We show that the activities of two Ets-related transcription factors required for normal eye development in Drosophila, pointed and yan, are regulated by the Ras1/MAPK pathway. The pointed gene codes for two related proteins, and we show that one form is a constitutive activator of transcription, while the activity of the other form is stimulated by the Ras1/MAPK pathway. Mutation of the single consensus MAPK phosphorylation site in the second form abrogates this responsiveness. yan is a negative regulator of photoreceptor determination, and genetic data suggest that it acts as an antagonist of Ras1. We demonstrate that yan can repress transcription and that this repression activity is negatively regulated by the Ras1/MAPK signal, most likely through direct phosphorylation of yan by MAPK.

The claustrum is one of the most widely connected regions of the forebrain, yet its function has remained obscure, largely due to the experimentally challenging nature of targeting this small, thin, and elongated brain area. However, recent advances in molecular techniques have enabled the anatomy and physiology of the claustrum to be studied with the spatiotemporal and cell type-specific precision required to eventually converge on what this area does. Here we review early anatomical and electrophysiological results from cats and primates, as well as recent work in the rodent, identifying the connectivity, cell types, and physiological circuit mechanisms underlying the communication between the claustrum and the cortex. The emerging picture is one in which the rodent claustrum is closely tied to frontal/limbic regions and plays a role in processes, such as attention, that are associated with these areas. Expected final online publication date for the , Volume 43 is July 8, 2020. Please see http://www.annualreviews.org/page/journal/pubdates for revised estimates.

The ability to adjust one's behavioral strategy in complex environments is at the core of cognition. Doing so efficiently requires monitoring the reliability of the ongoing strategy and, when appropriate, switching away from it to evaluate alternatives. Studies in humans and non-human primates have uncovered signals in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) that reflect the pressure to switch away from the ongoing strategy, whereas other ACC signals relate to the pursuit of alternatives. However, whether these signals underlie computations that actually underpin strategy switching or merely reflect tracking of related variables remains unclear. Here we provide causal evidence that the rodent ACC actively arbitrates between persisting with the ongoing behavioral strategy and temporarily switching away to re-evaluate alternatives. Furthermore, by individually perturbing distinct output pathways, we establish that the two associated computations-determining whether to switch strategy and committing to the pursuit of a specific alternative-are segregated in the ACC microcircuitry.

The argos gene encodes a protein that is required for viability and that regulates the determination of cells in the Drosophila eye. A developmental analysis of argos mutant eyes indicates that the mystery cells, which are usually nonneuronal, are transformed into extra photoreceptors, and that supernumerary cone cells and pigment cells are also recruited. Clonal analysis indicates that argos acts nonautonomously and can diffuse over the range of several cell diameters. Conceptual translation of the argos gene suggests that it encodes a secreted protein.

Reconstructing the genealogy of every cell that makes up an organism remains a long-standing challenge in developmental biology. Besides its relevance for understanding the mechanisms underlying normal and pathological development, resolving the lineage origin of cell types will be crucial to create these types on-demand. Multiple strategies have been deployed towards the problem of lineage tracing, ranging from direct observation to sophisticated genetic approaches. Here we discuss the achievements and limitations of past and current technology. Finally, we speculate about the future of lineage tracing and how to reach the next milestones in the field.

Reconstructing the genealogy of every cell that makes up an organism remains a long-standing challenge in developmental biology. Besides its relevance for understanding the mechanisms underlying normal and pathological development, resolving the lineage origin of cell types will be crucial to create these types on-demand. Multiple strategies have been deployed towards the problem of lineage tracing, ranging from direct observation to sophisticated genetic approaches. Here we discuss the achievements and limitations of past and current technology. Finally, we speculate about the future of lineage tracing and how to reach the next milestones in the field.

The basal ganglia plays a significant role in transforming activity in the cerebral cortex into directed behavior, involving motor learning, habit formation and the selection of actions based on desirable outcomes, and the organization of the basal ganglia is intimately linked to that of the cerebral cortex. In this chapter, we focus primarily on the neocortical part of the basal ganglia. A general canonical organizational plan of the neocortical-related basal ganglia is described. An understanding of the canonical organization of the neostriatal part of the basal ganglia, provides a framework for determining the general organizational principles of the parts of the basal ganglia connected with allocortical areas and the amygdala, and this is discussed. While it has been proposed that the basal ganglia provide interactions between disparate functional circuits, another approach might be that there are parallel functional circuits, in which distinct functions are for the most part maintained, or segregated, one from the other. This chapter, however, is biased toward the view that there is maintenance of functional parallel circuits in the organization of the basal ganglia, but that the circuit contains neuroanatomical features that provide for considerable interaction between adjacent circuits.

Vertebrates are remarkable for their ability to select and execute goal-directed actions: motor skills critical for thriving in complex, competitive environments. A key aspect of a motor skill is the ability to execute its component movements over a range of speeds, amplitudes and frequencies (vigor). Recent work has indicated that a subcortical circuit, the basal ganglia, is a critical determinant of movement vigor in rodents and primates. We propose that the basal ganglia evolved from a circuit that in lower vertebrates and some mammals is sufficient to directly command simple or stereotyped movements to one that indirectly controls the vigor of goal-directed movements. The implications of a dual role of the basal ganglia in the control of vigor and response to reward are also discussed.

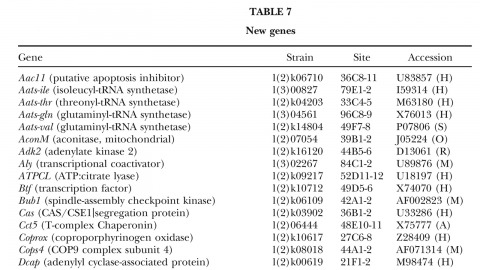

A fundamental goal of genetics and functional genomics is to identify and mutate every gene in model organisms such as Drosophila melanogaster. The Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project (BDGP) gene disruption project generates single P-element insertion strains that each mutate unique genomic open reading frames. Such strains strongly facilitate further genetic and molecular studies of the disrupted loci, but it has remained unclear if P elements can be used to mutate all Drosophila genes. We now report that the primary collection has grown to contain 1045 strains that disrupt more than 25% of the estimated 3600 Drosophila genes that are essential for adult viability. Of these P insertions, 67% have been verified by genetic tests to cause the associated recessive mutant phenotypes, and the validity of most of the remaining lines is predicted on statistical grounds. Sequences flanking >920 insertions have been determined to exactly position them in the genome and to identify 376 potentially affected transcripts from collections of EST sequences. Strains in the BDGP collection are available from the Bloomington Stock Center and have already assisted the research community in characterizing >250 Drosophila genes. The likely identity of 131 additional genes in the collection is reported here. Our results show that Drosophila genes have a wide range of sensitivity to inactivation by P elements, and provide a rationale for greatly expanding the BDGP primary collection based entirely on insertion site sequencing. We predict that this approach can bring >85% of all Drosophila open reading frames under experimental control.