Filter

Associated Lab

- Aguilera Castrejon Lab (17) Apply Aguilera Castrejon Lab filter

- Ahrens Lab (69) Apply Ahrens Lab filter

- Aso Lab (42) Apply Aso Lab filter

- Baker Lab (38) Apply Baker Lab filter

- Betzig Lab (115) Apply Betzig Lab filter

- Beyene Lab (14) Apply Beyene Lab filter

- Bock Lab (17) Apply Bock Lab filter

- Branson Lab (54) Apply Branson Lab filter

- Card Lab (43) Apply Card Lab filter

- Cardona Lab (64) Apply Cardona Lab filter

- Chklovskii Lab (13) Apply Chklovskii Lab filter

- Clapham Lab (15) Apply Clapham Lab filter

- Cui Lab (19) Apply Cui Lab filter

- Darshan Lab (12) Apply Darshan Lab filter

- Dennis Lab (2) Apply Dennis Lab filter

- Dickson Lab (46) Apply Dickson Lab filter

- Druckmann Lab (25) Apply Druckmann Lab filter

- Dudman Lab (53) Apply Dudman Lab filter

- Eddy/Rivas Lab (30) Apply Eddy/Rivas Lab filter

- Egnor Lab (11) Apply Egnor Lab filter

- Espinosa Medina Lab (21) Apply Espinosa Medina Lab filter

- Feliciano Lab (10) Apply Feliciano Lab filter

- Fetter Lab (41) Apply Fetter Lab filter

- FIB-SEM Technology (1) Apply FIB-SEM Technology filter

- Fitzgerald Lab (29) Apply Fitzgerald Lab filter

- Freeman Lab (15) Apply Freeman Lab filter

- Funke Lab (42) Apply Funke Lab filter

- Gonen Lab (91) Apply Gonen Lab filter

- Grigorieff Lab (62) Apply Grigorieff Lab filter

- Harris Lab (64) Apply Harris Lab filter

- Heberlein Lab (94) Apply Heberlein Lab filter

- Hermundstad Lab (30) Apply Hermundstad Lab filter

- Hess Lab (79) Apply Hess Lab filter

- Ilanges Lab (3) Apply Ilanges Lab filter

- Jayaraman Lab (48) Apply Jayaraman Lab filter

- Ji Lab (33) Apply Ji Lab filter

- Johnson Lab (6) Apply Johnson Lab filter

- Kainmueller Lab (19) Apply Kainmueller Lab filter

- Karpova Lab (14) Apply Karpova Lab filter

- Keleman Lab (13) Apply Keleman Lab filter

- Keller Lab (76) Apply Keller Lab filter

- Koay Lab (18) Apply Koay Lab filter

- Lavis Lab (154) Apply Lavis Lab filter

- Lee (Albert) Lab (34) Apply Lee (Albert) Lab filter

- Leonardo Lab (23) Apply Leonardo Lab filter

- Li Lab (30) Apply Li Lab filter

- Lippincott-Schwartz Lab (178) Apply Lippincott-Schwartz Lab filter

- Liu (Yin) Lab (7) Apply Liu (Yin) Lab filter

- Liu (Zhe) Lab (64) Apply Liu (Zhe) Lab filter

- Looger Lab (138) Apply Looger Lab filter

- Magee Lab (49) Apply Magee Lab filter

- Menon Lab (18) Apply Menon Lab filter

- Murphy Lab (13) Apply Murphy Lab filter

- O'Shea Lab (7) Apply O'Shea Lab filter

- Otopalik Lab (13) Apply Otopalik Lab filter

- Pachitariu Lab (49) Apply Pachitariu Lab filter

- Pastalkova Lab (18) Apply Pastalkova Lab filter

- Pavlopoulos Lab (19) Apply Pavlopoulos Lab filter

- Pedram Lab (15) Apply Pedram Lab filter

- Podgorski Lab (16) Apply Podgorski Lab filter

- Reiser Lab (54) Apply Reiser Lab filter

- Riddiford Lab (44) Apply Riddiford Lab filter

- Romani Lab (49) Apply Romani Lab filter

- Rubin Lab (148) Apply Rubin Lab filter

- Saalfeld Lab (64) Apply Saalfeld Lab filter

- Satou Lab (16) Apply Satou Lab filter

- Scheffer Lab (38) Apply Scheffer Lab filter

- Schreiter Lab (69) Apply Schreiter Lab filter

- Sgro Lab (21) Apply Sgro Lab filter

- Shroff Lab (31) Apply Shroff Lab filter

- Simpson Lab (23) Apply Simpson Lab filter

- Singer Lab (80) Apply Singer Lab filter

- Spruston Lab (97) Apply Spruston Lab filter

- Stern Lab (158) Apply Stern Lab filter

- Sternson Lab (54) Apply Sternson Lab filter

- Stringer Lab (39) Apply Stringer Lab filter

- Svoboda Lab (135) Apply Svoboda Lab filter

- Tebo Lab (35) Apply Tebo Lab filter

- Tervo Lab (9) Apply Tervo Lab filter

- Tillberg Lab (21) Apply Tillberg Lab filter

- Tjian Lab (64) Apply Tjian Lab filter

- Truman Lab (88) Apply Truman Lab filter

- Turaga Lab (53) Apply Turaga Lab filter

- Turner Lab (39) Apply Turner Lab filter

- Vale Lab (8) Apply Vale Lab filter

- Voigts Lab (4) Apply Voigts Lab filter

- Wang (Meng) Lab (27) Apply Wang (Meng) Lab filter

- Wang (Shaohe) Lab (25) Apply Wang (Shaohe) Lab filter

- Wu Lab (9) Apply Wu Lab filter

- Zlatic Lab (28) Apply Zlatic Lab filter

- Zuker Lab (25) Apply Zuker Lab filter

Associated Project Team

- CellMap (12) Apply CellMap filter

- COSEM (3) Apply COSEM filter

- FIB-SEM Technology (5) Apply FIB-SEM Technology filter

- Fly Descending Interneuron (12) Apply Fly Descending Interneuron filter

- Fly Functional Connectome (14) Apply Fly Functional Connectome filter

- Fly Olympiad (5) Apply Fly Olympiad filter

- FlyEM (56) Apply FlyEM filter

- FlyLight (50) Apply FlyLight filter

- GENIE (47) Apply GENIE filter

- Integrative Imaging (7) Apply Integrative Imaging filter

- Larval Olympiad (2) Apply Larval Olympiad filter

- MouseLight (18) Apply MouseLight filter

- NeuroSeq (1) Apply NeuroSeq filter

- ThalamoSeq (1) Apply ThalamoSeq filter

- Tool Translation Team (T3) (28) Apply Tool Translation Team (T3) filter

- Transcription Imaging (49) Apply Transcription Imaging filter

Publication Date

- 2025 (227) Apply 2025 filter

- 2024 (212) Apply 2024 filter

- 2023 (158) Apply 2023 filter

- 2022 (192) Apply 2022 filter

- 2021 (194) Apply 2021 filter

- 2020 (196) Apply 2020 filter

- 2019 (202) Apply 2019 filter

- 2018 (232) Apply 2018 filter

- 2017 (217) Apply 2017 filter

- 2016 (209) Apply 2016 filter

- 2015 (252) Apply 2015 filter

- 2014 (236) Apply 2014 filter

- 2013 (194) Apply 2013 filter

- 2012 (190) Apply 2012 filter

- 2011 (190) Apply 2011 filter

- 2010 (161) Apply 2010 filter

- 2009 (158) Apply 2009 filter

- 2008 (140) Apply 2008 filter

- 2007 (106) Apply 2007 filter

- 2006 (92) Apply 2006 filter

- 2005 (67) Apply 2005 filter

- 2004 (57) Apply 2004 filter

- 2003 (58) Apply 2003 filter

- 2002 (39) Apply 2002 filter

- 2001 (28) Apply 2001 filter

- 2000 (29) Apply 2000 filter

- 1999 (14) Apply 1999 filter

- 1998 (18) Apply 1998 filter

- 1997 (16) Apply 1997 filter

- 1996 (10) Apply 1996 filter

- 1995 (18) Apply 1995 filter

- 1994 (12) Apply 1994 filter

- 1993 (10) Apply 1993 filter

- 1992 (6) Apply 1992 filter

- 1991 (11) Apply 1991 filter

- 1990 (11) Apply 1990 filter

- 1989 (6) Apply 1989 filter

- 1988 (1) Apply 1988 filter

- 1987 (7) Apply 1987 filter

- 1986 (4) Apply 1986 filter

- 1985 (5) Apply 1985 filter

- 1984 (2) Apply 1984 filter

- 1983 (2) Apply 1983 filter

- 1982 (3) Apply 1982 filter

- 1981 (3) Apply 1981 filter

- 1980 (1) Apply 1980 filter

- 1979 (1) Apply 1979 filter

- 1976 (2) Apply 1976 filter

- 1973 (1) Apply 1973 filter

- 1970 (1) Apply 1970 filter

- 1967 (1) Apply 1967 filter

Type of Publication

4202 Publications

Showing 2161-2170 of 4202 resultsAn agglomerative clustering algorithm merges the most similar pair of clusters at every iteration. The function that evaluates similarity is traditionally handdesigned, but there has been recent interest in supervised or semisupervised settings in which ground-truth clustered data is available for training. Here we show how to train a similarity function by regarding it as the action-value function of a reinforcement learning problem. We apply this general method to segment images by clustering superpixels, an application that we call Learning to Agglomerate Superpixel Hierarchies (LASH). When applied to a challenging dataset of brain images from serial electron microscopy, LASH dramatically improved segmentation accuracy when clustering supervoxels generated by state of the boundary detection algorithms. The naive strategy of directly training only supervoxel similarities and applying single linkage clustering produced less improvement.

Manifold attractors are a key framework for understanding how continuous variables, such as position or head direction, are encoded in the brain. In this framework, the variable is represented along a continuum of persistent neuronal states which forms a manifold attactor. Neural networks with symmetric synaptic connectivity that can implement manifold attractors have become the dominant model in this framework. In addition to a symmetric connectome, these networks imply homogeneity of individual-neuron tuning curves and symmetry of the representational space; these features are largely inconsistent with neurobiological data. Here, we developed a theory for computations based on manifold attractors in trained neural networks and show how these manifolds can cope with diverse neuronal responses, imperfections in the geometry of the manifold and a high level of synaptic heterogeneity. In such heterogeneous trained networks, a continuous representational space emerges from a small set of stimuli used for training. Furthermore, we find that the network response to external inputs depends on the geometry of the representation and on the level of synaptic heterogeneity in an analytically tractable and interpretable way. Finally, we show that a too complex geometry of the neuronal representation impairs the attractiveness of the manifold and may lead to its destabilization. Our framework reveals that continuous features can be represented in the recurrent dynamics of heterogeneous networks without assuming unrealistic symmetry. It suggests that the representational space of putative manifold attractors in the brain dictates the dynamics in their vicinity.

We present a dynamic nonlinear generative model for visual motion based on a latent representation of binary-gated Gaussian variables. Trained on sequences of images, the model learns to represent different movement directions in different variables. We use an online approximate-inference scheme that can be mapped to the dynamics of networks of neurons. Probed with drifting grating stimuli and moving bars of light, neurons in the model show patterns of responses analogous to those of direction-selective simple cells in primary visual cortex. Most model neurons also show speed tuning and respond equally well to a range of motion directions and speeds aligned to the constraint line of their respective preferred speed. We show how these computations are enabled by a specific pattern of recurrent connections learned by the model.

The performance of information processing systems, from artificial neural networks to natural neuronal ensembles, depends heavily on the underlying system architecture. In this study, we compare the performance of parallel and layered network architectures during sequential tasks that require both acquisition and retention of information, thereby identifying tradeoffs between learning and memory processes. During the task of supervised, sequential function approximation, networks produce and adapt representations of external information. Performance is evaluated by statistically analyzing the error in these representations while varying the initial network state, the structure of the external information, and the time given to learn the information. We link performance to complexity in network architecture by characterizing local error landscape curvature. We find that variations in error landscape structure give rise to tradeoffs in performance; these include the ability of the network to maximize accuracy versus minimize inaccuracy and produce specific versus generalizable representations of information. Parallel networks generate smooth error landscapes with deep, narrow minima, enabling them to find highly specific representations given sufficient time. While accurate, however, these representations are difficult to generalize. In contrast, layered networks generate rough error landscapes with a variety of local minima, allowing them to quickly find coarse representations. Although less accurate, these representations are easily adaptable. The presence of measurable performance tradeoffs in both layered and parallel networks has implications for understanding the behavior of a wide variety of natural and artificial learning systems.

Cortical neurons form specific circuits, but the functional structure of this microarchitecture and its relation to behaviour are poorly understood. Two-photon calcium imaging can monitor activity of spatially defined neuronal ensembles in the mammalian cortex. Here we applied this technique to the motor cortex of mice performing a choice behaviour. Head-fixed mice were trained to lick in response to one of two odours, and to withhold licking for the other odour. Mice routinely showed significant learning within the first behavioural session and across sessions. Microstimulation and trans-synaptic tracing identified two non-overlapping candidate tongue motor cortical areas. Inactivating either area impaired voluntary licking. Imaging in layer 2/3 showed neurons with diverse response types in both areas. Activity in approximately half of the imaged neurons distinguished trial types associated with different actions. Many neurons showed modulation coinciding with or preceding the action, consistent with their involvement in motor control. Neurons with different response types were spatially intermingled. Nearby neurons (within approximately 150 mum) showed pronounced coincident activity. These temporal correlations increased with learning within and across behavioural sessions, specifically for neuron pairs with similar response types. We propose that correlated activity in specific ensembles of functionally related neurons is a signature of learning-related circuit plasticity. Our findings reveal a fine-scale and dynamic organization of the frontal cortex that probably underlies flexible behaviour.

Olfactory memories can be very good-your mother's baking-or very bad-your father's cooking. We go through life forming these different associations with the smells we encounter. But what makes one association pleasant and another repulsive? Work in deep areas of the Drosophila brain has revealed the beginnings of an answer, as reported in this issue of Neuron by Owald et al. (2015).

Two simple models—vaulting over stiff legs and rebounding over compliant legs—are employed to describe the mechanics of legged locomotion. It is agreed that compliant legs are necessary for describing running, and that leg compliance is also present during walking. Stiff legs continue to be employed to model walking under the assumption that the compliance of the leg during walking is low enough to be considered stiff. Here we study gait choice and walk-to-run transition in a biped with compliance and show that the principles underlying gait choice and transition are completely different from stiff legs. Two findings underpin our conclusions: First, at the same speed, step length and stance duration, multiple gaits that differ in the number of times the leg expands and contracts during a single stance are possible. Among them, humans and other animals choose the (normal) gait with M-shaped vertical ground reaction forces (vGRF) not just because of energy considerations but also constraints from forces. Second, the transition from walking to running occurs because of three factors: vGRF minimum at mid-stance characteristic of normal walking, synchronization of horizontal and vertical motions during single support, and velocity redirection during the double support. The insight above required an analytical approximation of the double spring-loaded pendulum (DSLIP) model describing the intricate oscillatory dynamics that relate single and double support phases. Additionally, we also examined DSLIP as a quantitative model for locomotion and conclude that DSLIP speed range is limited. However, insights gleaned from the analytical treatment of DSLIP are general and will inform the construction of more accurate models of walking. bioRxiv preprint: https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.09.23.612940

Leptin is an adipose tissue hormone that maintains homeostatic control of adipose tissue mass by regulating the activity of specific neural populations controlling appetite and metabolism1. Leptin regulates food intake by inhibiting orexigenic agouti-related protein (AGRP) neurons and activating anorexigenic pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons2. However, while AGRP neurons regulate food intake on a rapid time scale, acute activation of POMC neurons has only a minimal effect3–5. This has raised the possibility that there is a heretofore unidentified leptin-regulated neural population that suppresses appetite on a rapid time scale. Here, we report the discovery of a novel population of leptin-target neurons expressing basonuclin 2 (Bnc2) that acutely suppress appetite by directly inhibiting AGRP neurons. Opposite to the effect of AGRP activation, BNC2 neuronal activation elicited a place preference indicative of positive valence in hungry but not fed mice. The activity of BNC2 neurons is finely tuned by leptin, sensory food cues, and nutritional status. Finally, deleting leptin receptors in BNC2 neurons caused marked hyperphagia and obesity, similar to that observed in a leptin receptor knockout in AGRP neurons. These data indicate that BNC2-expressing neurons are a key component of the neural circuit that maintains energy balance, thus filling an important gap in our understanding of the regulation of food intake and leptin action.

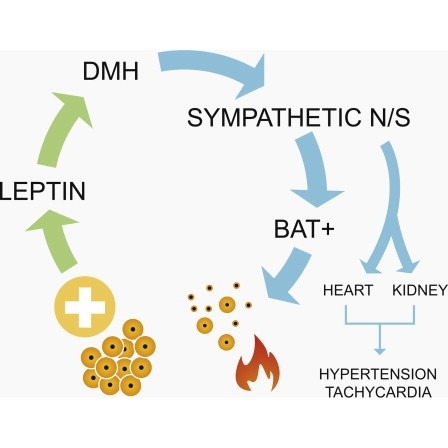

Obesity is associated with increased blood pressure (BP), which in turn increases the risk of cardiovascular diseases. We found that the increase in leptin levels seen in diet-induced obesity (DIO) drives an increase in BP in rodents, an effect that was not seen in animals deficient in leptin or leptin receptors (LepR). Furthermore, humans with loss-of-function mutations in leptin and the LepR have low BP despite severe obesity. Leptin's effects on BP are mediated by neuronal circuits in the dorsomedial hypothalamus (DMH), as blocking leptin with a specific antibody, antagonist, or inhibition of the activity of LepR-expressing neurons in the DMH caused a rapid reduction of BP in DIO mice, independent of changes in weight. Re-expression of LepRs in the DMH of DIO LepR-deficient mice caused an increase in BP. These studies demonstrate that leptin couples changes in weight to changes in BP in mammalian species.

The central actions of leptin are essential for homeostatic control of adipose tissue mass, glucose metabolism, and many autonomic and neuroendocrine systems. In the brain, leptin acts on numerous different cell types via the long-form leptin receptor (LepRb) to elicit its effects. The precise identification of leptin’s cellular targets is fundamental to understanding the mechanism of its pleiotropic central actions. We have systematically characterized LepRb distribution in the mouse brain using in situ hybridization in wildtype mice as well as by EYFP immunoreactivity in a novel LepRb-IRES-Cre EYFP reporter mouse line showing high levels of LepRb mRNA/EYFP coexpression. We found substantial LepRb mRNA and EYFP expression in hypothalamic and extrahypothalamic sites described before, including the dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus, ventral premammillary nucleus, ventral tegmental area, parabrachial nucleus, and the dorsal vagal complex. Expression in insular cortex, lateral septal nucleus, medial preoptic area, rostral linear nucleus, and in the Edinger-Westphal nucleus was also observed and had been previously unreported. The LepRb-IRES-Cre reporter line was used to chemically characterize a population of leptin receptor-expressing neurons in the midbrain. Tyrosine hydroxylase and Cre reporter were found to be coexpressed in the ventral tegmental area and in other midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Lastly, the LepRb-IRES-Cre reporter line was used to map the extent of peripheral leptin sensing by central nervous system (CNS) LepRb neurons. Thus, we provide data supporting the use of the LepRb-IRES-Cre line for the assessment of the anatomic and functional characteristics of neurons expressing leptin receptor.