Filter

Associated Lab

- Aguilera Castrejon Lab (2) Apply Aguilera Castrejon Lab filter

- Ahrens Lab (58) Apply Ahrens Lab filter

- Aso Lab (42) Apply Aso Lab filter

- Baker Lab (19) Apply Baker Lab filter

- Betzig Lab (103) Apply Betzig Lab filter

- Beyene Lab (10) Apply Beyene Lab filter

- Bock Lab (14) Apply Bock Lab filter

- Branson Lab (51) Apply Branson Lab filter

- Card Lab (37) Apply Card Lab filter

- Cardona Lab (45) Apply Cardona Lab filter

- Chklovskii Lab (10) Apply Chklovskii Lab filter

- Clapham Lab (14) Apply Clapham Lab filter

- Cui Lab (19) Apply Cui Lab filter

- Darshan Lab (8) Apply Darshan Lab filter

- Dennis Lab (1) Apply Dennis Lab filter

- Dickson Lab (32) Apply Dickson Lab filter

- Druckmann Lab (21) Apply Druckmann Lab filter

- Dudman Lab (41) Apply Dudman Lab filter

- Eddy/Rivas Lab (30) Apply Eddy/Rivas Lab filter

- Egnor Lab (4) Apply Egnor Lab filter

- Espinosa Medina Lab (18) Apply Espinosa Medina Lab filter

- Feliciano Lab (10) Apply Feliciano Lab filter

- Fetter Lab (31) Apply Fetter Lab filter

- FIB-SEM Technology (1) Apply FIB-SEM Technology filter

- Fitzgerald Lab (16) Apply Fitzgerald Lab filter

- Freeman Lab (15) Apply Freeman Lab filter

- Funke Lab (42) Apply Funke Lab filter

- Gonen Lab (59) Apply Gonen Lab filter

- Grigorieff Lab (34) Apply Grigorieff Lab filter

- Harris Lab (55) Apply Harris Lab filter

- Heberlein Lab (13) Apply Heberlein Lab filter

- Hermundstad Lab (26) Apply Hermundstad Lab filter

- Hess Lab (76) Apply Hess Lab filter

- Ilanges Lab (3) Apply Ilanges Lab filter

- Jayaraman Lab (44) Apply Jayaraman Lab filter

- Ji Lab (33) Apply Ji Lab filter

- Johnson Lab (1) Apply Johnson Lab filter

- Karpova Lab (13) Apply Karpova Lab filter

- Keleman Lab (8) Apply Keleman Lab filter

- Keller Lab (61) Apply Keller Lab filter

- Koay Lab (3) Apply Koay Lab filter

- Lavis Lab (144) Apply Lavis Lab filter

- Lee (Albert) Lab (29) Apply Lee (Albert) Lab filter

- Leonardo Lab (19) Apply Leonardo Lab filter

- Li Lab (6) Apply Li Lab filter

- Lippincott-Schwartz Lab (107) Apply Lippincott-Schwartz Lab filter

- Liu (Yin) Lab (2) Apply Liu (Yin) Lab filter

- Liu (Zhe) Lab (59) Apply Liu (Zhe) Lab filter

- Looger Lab (137) Apply Looger Lab filter

- Magee Lab (31) Apply Magee Lab filter

- Menon Lab (12) Apply Menon Lab filter

- Murphy Lab (6) Apply Murphy Lab filter

- O'Shea Lab (6) Apply O'Shea Lab filter

- Otopalik Lab (1) Apply Otopalik Lab filter

- Pachitariu Lab (39) Apply Pachitariu Lab filter

- Pastalkova Lab (5) Apply Pastalkova Lab filter

- Pavlopoulos Lab (7) Apply Pavlopoulos Lab filter

- Pedram Lab (4) Apply Pedram Lab filter

- Podgorski Lab (16) Apply Podgorski Lab filter

- Reiser Lab (49) Apply Reiser Lab filter

- Riddiford Lab (20) Apply Riddiford Lab filter

- Romani Lab (39) Apply Romani Lab filter

- Rubin Lab (110) Apply Rubin Lab filter

- Saalfeld Lab (47) Apply Saalfeld Lab filter

- Satou Lab (1) Apply Satou Lab filter

- Scheffer Lab (38) Apply Scheffer Lab filter

- Schreiter Lab (52) Apply Schreiter Lab filter

- Sgro Lab (2) Apply Sgro Lab filter

- Shroff Lab (31) Apply Shroff Lab filter

- Simpson Lab (18) Apply Simpson Lab filter

- Singer Lab (37) Apply Singer Lab filter

- Spruston Lab (61) Apply Spruston Lab filter

- Stern Lab (75) Apply Stern Lab filter

- Sternson Lab (47) Apply Sternson Lab filter

- Stringer Lab (36) Apply Stringer Lab filter

- Svoboda Lab (132) Apply Svoboda Lab filter

- Tebo Lab (11) Apply Tebo Lab filter

- Tervo Lab (9) Apply Tervo Lab filter

- Tillberg Lab (18) Apply Tillberg Lab filter

- Tjian Lab (17) Apply Tjian Lab filter

- Truman Lab (58) Apply Truman Lab filter

- Turaga Lab (41) Apply Turaga Lab filter

- Turner Lab (27) Apply Turner Lab filter

- Vale Lab (8) Apply Vale Lab filter

- Voigts Lab (4) Apply Voigts Lab filter

- Wang (Meng) Lab (27) Apply Wang (Meng) Lab filter

- Wang (Shaohe) Lab (6) Apply Wang (Shaohe) Lab filter

- Wong-Campos Lab (1) Apply Wong-Campos Lab filter

- Wu Lab (8) Apply Wu Lab filter

- Zlatic Lab (26) Apply Zlatic Lab filter

- Zuker Lab (5) Apply Zuker Lab filter

Associated Project Team

- CellMap (12) Apply CellMap filter

- COSEM (3) Apply COSEM filter

- FIB-SEM Technology (5) Apply FIB-SEM Technology filter

- Fly Descending Interneuron (12) Apply Fly Descending Interneuron filter

- Fly Functional Connectome (14) Apply Fly Functional Connectome filter

- Fly Olympiad (5) Apply Fly Olympiad filter

- FlyEM (56) Apply FlyEM filter

- FlyLight (50) Apply FlyLight filter

- GENIE (47) Apply GENIE filter

- Integrative Imaging (9) Apply Integrative Imaging filter

- Larval Olympiad (2) Apply Larval Olympiad filter

- MouseLight (18) Apply MouseLight filter

- NeuroSeq (1) Apply NeuroSeq filter

- ThalamoSeq (1) Apply ThalamoSeq filter

- Tool Translation Team (T3) (29) Apply Tool Translation Team (T3) filter

- Transcription Imaging (45) Apply Transcription Imaging filter

Associated Support Team

- Project Pipeline Support (5) Apply Project Pipeline Support filter

- Anatomy and Histology (18) Apply Anatomy and Histology filter

- Cryo-Electron Microscopy (41) Apply Cryo-Electron Microscopy filter

- Electron Microscopy (18) Apply Electron Microscopy filter

- Gene Targeting and Transgenics (11) Apply Gene Targeting and Transgenics filter

- High Performance Computing (7) Apply High Performance Computing filter

- Integrative Imaging (18) Apply Integrative Imaging filter

- Invertebrate Shared Resource (40) Apply Invertebrate Shared Resource filter

- Janelia Experimental Technology (37) Apply Janelia Experimental Technology filter

- Management Team (1) Apply Management Team filter

- Mass Spectrometry (1) Apply Mass Spectrometry filter

- Molecular Genomics (15) Apply Molecular Genomics filter

- Primary & iPS Cell Culture (14) Apply Primary & iPS Cell Culture filter

- Project Technical Resources (53) Apply Project Technical Resources filter

- Quantitative Genomics (20) Apply Quantitative Genomics filter

- Scientific Computing (100) Apply Scientific Computing filter

- Viral Tools (14) Apply Viral Tools filter

- Vivarium (7) Apply Vivarium filter

Publication Date

- 2026 (17) Apply 2026 filter

- 2025 (225) Apply 2025 filter

- 2024 (211) Apply 2024 filter

- 2023 (157) Apply 2023 filter

- 2022 (166) Apply 2022 filter

- 2021 (175) Apply 2021 filter

- 2020 (177) Apply 2020 filter

- 2019 (177) Apply 2019 filter

- 2018 (206) Apply 2018 filter

- 2017 (186) Apply 2017 filter

- 2016 (191) Apply 2016 filter

- 2015 (195) Apply 2015 filter

- 2014 (190) Apply 2014 filter

- 2013 (136) Apply 2013 filter

- 2012 (112) Apply 2012 filter

- 2011 (98) Apply 2011 filter

- 2010 (61) Apply 2010 filter

- 2009 (56) Apply 2009 filter

- 2008 (40) Apply 2008 filter

- 2007 (21) Apply 2007 filter

- 2006 (3) Apply 2006 filter

2800 Janelia Publications

Showing 2241-2250 of 2800 resultsEnhancer-binding pluripotency regulators (Sox2 and Oct4) play a seminal role in embryonic stem (ES) cell-specific gene regulation. Here, we combine in vivo and in vitro single-molecule imaging, transcription factor (TF) mutagenesis, and ChIP-exo mapping to determine how TFs dynamically search for and assemble on their cognate DNA target sites. We find that enhanceosome assembly is hierarchically ordered with kinetically favored Sox2 engaging the target DNA first, followed by assisted binding of Oct4. Sox2/Oct4 follow a trial-and-error sampling mechanism involving 84-97 events of 3D diffusion (3.3-3.7 s) interspersed with brief nonspecific collisions (0.75-0.9 s) before acquiring and dwelling at specific target DNA (12.0-14.6 s). Sox2 employs a 3D diffusion-dominated search mode facilitated by 1D sliding along open DNA to efficiently locate targets. Our findings also reveal fundamental aspects of gene and developmental regulation by fine-tuning TF dynamics and influence of the epigenome on target search parameters.

Conserved ATP-dependent chromatin remodelers establish and maintain genome-wide chromatin architectures of regulatory DNA during cellular lifespan, but the temporal interactions between remodelers and chromatin targets have been obscure. We performed live-cell single-molecule tracking for RSC, SWI/SNF, CHD1, ISW1, ISW2, and INO80 remodeling complexes in budding yeast and detected hyperkinetic behaviors for chromatin-bound molecules that frequently transition to the free state for all complexes. Chromatin-bound remodelers display notably higher diffusion than nucleosomal histones, and strikingly fast dissociation kinetics with 4-7 s mean residence times. These enhanced dynamics require ATP binding or hydrolysis by the catalytic ATPase, uncovering an additional function to its established role in nucleosome remodeling. Kinetic simulations show that multiple remodelers can repeatedly occupy the same promoter region on a timescale of minutes, implicating an unending 'tug-of-war' that controls a temporally shifting window of accessibility for the transcription initiation machinery.

Targeting of mRNAs to neuronal dendrites and axons plays an integral role in intracellular signaling, development, and synaptic plasticity. Single-molecule imaging of mRNAs in neurons and brain tissue has led to enhanced understanding of mRNA dynamics. Here we discuss aspects of mRNA regulation as revealed by single-molecule detection, which has led to quantitative analyses of mRNA diversity, localization, transport, and translation. These exciting new discoveries propel our understanding of the life of an mRNA in a neuron and how its activity is regulated at the single-molecule level.

Gene regulation relies on transcription factors (TFs) exploring the nucleus searching their targets. So far, most studies have focused on how fast TFs diffuse, underestimating the role of nuclear architecture. We implemented a single-molecule tracking assay to determine TFs dynamics. We found that c-Myc is a global explorer of the nucleus. In contrast, the positive transcription elongation factor P-TEFb is a local explorer that oversamples its environment. Consequently, each c-Myc molecule is equally available for all nuclear sites while P-TEFb reaches its targets in a position-dependent manner. Our observations are consistent with a model in which the exploration geometry of TFs is restrained by their interactions with nuclear structures and not by exclusion. The geometry-controlled kinetics of TFs target-search illustrates the influence of nuclear architecture on gene regulation, and has strong implications on how proteins react in the nucleus and how their function can be regulated in space and time.

Transcription is an inherently stochastic, noisy, and multi-step process, in which fluctuations at every step can cause variations in RNA synthesis, and affect physiology and differentiation decisions in otherwise identical cells. However, it has been an experimental challenge to directly link the stochastic events at the promoter to transcript production. Here we established a fast fluorescence in situ hybridization (fastFISH) method that takes advantage of intrinsically unstructured nucleic acid sequences to achieve exceptionally fast rates of specific hybridization (\~{}10e7 M(-1)s(-1)), and allows deterministic detection of single nascent transcripts. Using a prototypical RNA polymerase, we demonstrated the use of fastFISH to measure the kinetic rates of promoter escape, elongation, and termination in one assay at the single-molecule level, at sub-second temporal resolution. The principles of fastFISH design can be used to study stochasticity in gene regulation, to select targets for gene silencing, and to design nucleic acid nanostructures. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.01775.001.

Reconstruction of the axonal projection patterns of single neurons has been an important tool for understanding both the diversity of cell types in the brain and the logic of information flow between brain regions. Innovative approaches now enable the complete reconstruction of axonal projection patterns of individual neurons with vastly increased throughput. Here we review how advances in genetic, imaging, and computational techniques have been exploited for axonal reconstruction. We also discuss how new innovations could enable the integration of genetic and physiological information with axonal morphology for producing a census of cell types in the mammalian brain at scale. This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

AMPA-type receptors are transported large distances to support synaptic plasticity at distal dendritic locations. Studying the motion of AMPA receptor+ vesicles can improve our understanding of the mechanisms that underlie learning and memory. Nevertheless, technical challenges that prevent the visualization of AMPA receptor+vesicles limit our ability to study how these vesicles are trafficked. Existing methods rely on the overexpression of fluorescent protein-tagged AMPA receptors from plasmids, resulting in a saturated signal that obscures vesicles. Photobleaching must be applied to detect individual AMPA receptor+ vesicles, which may eliminate important vesicle populations from analysis. Here, we present a protocol to study AMPA receptor+ vesicles that addresses these challenges by 1) tagging AMPA receptors expressed from native loci with HaloTag and 2) employing a block-and-chase strategy with Janelia Fluor-conjugated HaloTag ligand to achieve sparse AMPA receptor labeling that obviates the need for photobleaching. After timelapse imaging is performed, AMPA receptor+ vesicles can be identified during image analysis, and their motion can be characterized using a single-particle tracking pipeline. Key features • Track and characterize the motion of AMPAR GluA1+ vesicles in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. • GluA1 tagged with HaloTag (GluA1-HT) is expressed from native Gria1 loci to avoid overexpression. • Sparse GluA1-HT labeling densities can be achieved without photobleaching via a block-and-chase strategy that utilizes Janelia Fluor (JF) dyes conjugated to HaloTag ligand (HTL). • GluA1-HT+ vesicles are identified during image analysis, and their motion is characterized using single-particle tracking (SPT) and hidden Markov modeling with Bayesian model selection (HMM-Bayes).

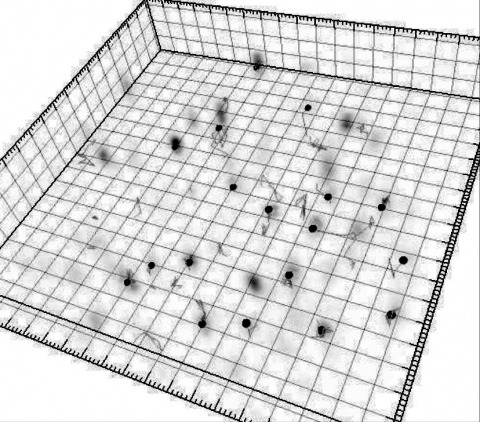

We present an approach to study macromolecular assemblies by detecting component proteins' characteristic high-resolution projection patterns, calculated from their known 3D structures, in single electron cryo-micrographs. Our method detects single apoferritin molecules in vitreous ice with high specificity and determines their orientation and location precisely. Simulations show that high spatial-frequency information and-in the presence of protein background-a whitening filter are essential for optimal detection, in particular for images taken far from focus. Experimentally, we could detect small viral RNA polymerase molecules, distributed randomly among binding locations, inside rotavirus particles. Based on the currently attainable image quality, we estimate a threshold for detection that is 150 kDa in ice and 300 kDa in 100 nm thick samples of dense biological material.

Once secretory proteins have been targeted to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) lumen, the proteins typically remain partitioned from the cytosol. If the secretory proteins misfold, they can be unfolded and retrotranslocated into the cytosol for destruction by the proteasome by ER-associated protein Degradation (ERAD). Here, we report that correctly folded and targeted luminal ER fluorescent protein reporters accumulate in the cytosol during acute misfolded secretory protein stress in yeast. Photoactivation fluorescence microscopy experiments reveal that luminal reporters already localized to the ER relocalize to the cytosol, even in the absence of essential ERAD machinery. We named this process "ER reflux." Reflux appears to be regulated in a size-dependent manner for reporters. Interestingly, prior heat shock stress also prevents ER stress-induced reflux. Together, our findings establish a new ER stress-regulated pathway for relocalization of small luminal secretory proteins into the cytosol, distinct from the ERAD and pre-emptive quality control pathways. Importantly, our results highlight the value of fully characterizing the cell biology of reporters and describe a simple modification to maintain luminal ER reporters in the ER during acute ER stress. This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

Accumulating evidence indicates that biological aging can be accelerated by environmental exposures, collectively called the 'exposome'. The skin, as the largest and most exposed organ, can be viewed as a 'window' for the deep exploration of the exposome and its effects on systemic aging. The complex interplay across hallmarks of aging in the skin and systemic biological aging suggests that physiological processes associated with skin aging influence, and are influenced by, systemic hallmarks of aging. This bidirectional relationship provides potential avenues for the prevention of accelerated biological aging and the identification of therapeutic targets. We provide a review of the interactions between skin exposure, aging hallmarks in the skin and associated systemic changes, and their implications in treatment and disease. We also discuss key questions that need to be addressed to maintain skin and overall health, highlighting the need for the development of precise biomarkers and advanced skin models.