Filter

Associated Lab

- Aguilera Castrejon Lab (2) Apply Aguilera Castrejon Lab filter

- Ahrens Lab (61) Apply Ahrens Lab filter

- Aso Lab (42) Apply Aso Lab filter

- Baker Lab (19) Apply Baker Lab filter

- Betzig Lab (103) Apply Betzig Lab filter

- Beyene Lab (10) Apply Beyene Lab filter

- Bock Lab (14) Apply Bock Lab filter

- Branson Lab (51) Apply Branson Lab filter

- Card Lab (37) Apply Card Lab filter

- Cardona Lab (45) Apply Cardona Lab filter

- Chklovskii Lab (10) Apply Chklovskii Lab filter

- Clapham Lab (14) Apply Clapham Lab filter

- Cui Lab (19) Apply Cui Lab filter

- Darshan Lab (8) Apply Darshan Lab filter

- Dennis Lab (1) Apply Dennis Lab filter

- Dickson Lab (32) Apply Dickson Lab filter

- Druckmann Lab (21) Apply Druckmann Lab filter

- Dudman Lab (41) Apply Dudman Lab filter

- Eddy/Rivas Lab (30) Apply Eddy/Rivas Lab filter

- Egnor Lab (4) Apply Egnor Lab filter

- Espinosa Medina Lab (19) Apply Espinosa Medina Lab filter

- Feliciano Lab (12) Apply Feliciano Lab filter

- Fetter Lab (31) Apply Fetter Lab filter

- FIB-SEM Technology (1) Apply FIB-SEM Technology filter

- Fitzgerald Lab (16) Apply Fitzgerald Lab filter

- Freeman Lab (15) Apply Freeman Lab filter

- Funke Lab (42) Apply Funke Lab filter

- Gonen Lab (59) Apply Gonen Lab filter

- Grigorieff Lab (34) Apply Grigorieff Lab filter

- Harris Lab (55) Apply Harris Lab filter

- Heberlein Lab (13) Apply Heberlein Lab filter

- Hermundstad Lab (26) Apply Hermundstad Lab filter

- Hess Lab (76) Apply Hess Lab filter

- Ilanges Lab (3) Apply Ilanges Lab filter

- Jayaraman Lab (44) Apply Jayaraman Lab filter

- Ji Lab (33) Apply Ji Lab filter

- Johnson Lab (1) Apply Johnson Lab filter

- Karpova Lab (13) Apply Karpova Lab filter

- Keleman Lab (8) Apply Keleman Lab filter

- Keller Lab (61) Apply Keller Lab filter

- Koay Lab (3) Apply Koay Lab filter

- Lavis Lab (144) Apply Lavis Lab filter

- Lee (Albert) Lab (29) Apply Lee (Albert) Lab filter

- Leonardo Lab (19) Apply Leonardo Lab filter

- Li Lab (6) Apply Li Lab filter

- Lippincott-Schwartz Lab (108) Apply Lippincott-Schwartz Lab filter

- Liu (Yin) Lab (3) Apply Liu (Yin) Lab filter

- Liu (Zhe) Lab (59) Apply Liu (Zhe) Lab filter

- Looger Lab (137) Apply Looger Lab filter

- Magee Lab (31) Apply Magee Lab filter

- Menon Lab (12) Apply Menon Lab filter

- Murphy Lab (6) Apply Murphy Lab filter

- O'Shea Lab (6) Apply O'Shea Lab filter

- Otopalik Lab (1) Apply Otopalik Lab filter

- Pachitariu Lab (40) Apply Pachitariu Lab filter

- Pastalkova Lab (5) Apply Pastalkova Lab filter

- Pavlopoulos Lab (7) Apply Pavlopoulos Lab filter

- Pedram Lab (4) Apply Pedram Lab filter

- Podgorski Lab (16) Apply Podgorski Lab filter

- Reiser Lab (49) Apply Reiser Lab filter

- Riddiford Lab (20) Apply Riddiford Lab filter

- Romani Lab (39) Apply Romani Lab filter

- Rubin Lab (111) Apply Rubin Lab filter

- Saalfeld Lab (47) Apply Saalfeld Lab filter

- Satou Lab (3) Apply Satou Lab filter

- Scheffer Lab (38) Apply Scheffer Lab filter

- Schreiter Lab (53) Apply Schreiter Lab filter

- Sgro Lab (2) Apply Sgro Lab filter

- Shroff Lab (31) Apply Shroff Lab filter

- Simpson Lab (18) Apply Simpson Lab filter

- Singer Lab (37) Apply Singer Lab filter

- Spruston Lab (61) Apply Spruston Lab filter

- Stern Lab (75) Apply Stern Lab filter

- Sternson Lab (47) Apply Sternson Lab filter

- Stringer Lab (38) Apply Stringer Lab filter

- Svoboda Lab (132) Apply Svoboda Lab filter

- Tebo Lab (11) Apply Tebo Lab filter

- Tervo Lab (9) Apply Tervo Lab filter

- Tillberg Lab (19) Apply Tillberg Lab filter

- Tjian Lab (17) Apply Tjian Lab filter

- Truman Lab (58) Apply Truman Lab filter

- Turaga Lab (41) Apply Turaga Lab filter

- Turner Lab (27) Apply Turner Lab filter

- Vale Lab (8) Apply Vale Lab filter

- Voigts Lab (4) Apply Voigts Lab filter

- Wang (Meng) Lab (27) Apply Wang (Meng) Lab filter

- Wang (Shaohe) Lab (6) Apply Wang (Shaohe) Lab filter

- Wong-Campos Lab (1) Apply Wong-Campos Lab filter

- Wu Lab (8) Apply Wu Lab filter

- Zlatic Lab (26) Apply Zlatic Lab filter

- Zuker Lab (5) Apply Zuker Lab filter

Associated Project Team

- CellMap (12) Apply CellMap filter

- COSEM (3) Apply COSEM filter

- FIB-SEM Technology (5) Apply FIB-SEM Technology filter

- Fly Descending Interneuron (12) Apply Fly Descending Interneuron filter

- Fly Functional Connectome (14) Apply Fly Functional Connectome filter

- Fly Olympiad (5) Apply Fly Olympiad filter

- FlyEM (56) Apply FlyEM filter

- FlyLight (50) Apply FlyLight filter

- GENIE (47) Apply GENIE filter

- Integrative Imaging (9) Apply Integrative Imaging filter

- Larval Olympiad (2) Apply Larval Olympiad filter

- MouseLight (18) Apply MouseLight filter

- NeuroSeq (1) Apply NeuroSeq filter

- ThalamoSeq (1) Apply ThalamoSeq filter

- Tool Translation Team (T3) (29) Apply Tool Translation Team (T3) filter

- Transcription Imaging (45) Apply Transcription Imaging filter

Associated Support Team

- Project Pipeline Support (5) Apply Project Pipeline Support filter

- Anatomy and Histology (18) Apply Anatomy and Histology filter

- Cryo-Electron Microscopy (41) Apply Cryo-Electron Microscopy filter

- Electron Microscopy (18) Apply Electron Microscopy filter

- Gene Targeting and Transgenics (11) Apply Gene Targeting and Transgenics filter

- High Performance Computing (7) Apply High Performance Computing filter

- Integrative Imaging (18) Apply Integrative Imaging filter

- Invertebrate Shared Resource (40) Apply Invertebrate Shared Resource filter

- Janelia Experimental Technology (37) Apply Janelia Experimental Technology filter

- Management Team (1) Apply Management Team filter

- Mass Spectrometry (1) Apply Mass Spectrometry filter

- Molecular Genomics (15) Apply Molecular Genomics filter

- Project Technical Resources (54) Apply Project Technical Resources filter

- Quantitative Genomics (20) Apply Quantitative Genomics filter

- Scientific Computing (102) Apply Scientific Computing filter

- Stem Cell & Primary Culture (14) Apply Stem Cell & Primary Culture filter

- Viral Tools (14) Apply Viral Tools filter

- Vivarium (7) Apply Vivarium filter

Publication Date

- 2026 (27) Apply 2026 filter

- 2025 (224) Apply 2025 filter

- 2024 (211) Apply 2024 filter

- 2023 (157) Apply 2023 filter

- 2022 (166) Apply 2022 filter

- 2021 (175) Apply 2021 filter

- 2020 (177) Apply 2020 filter

- 2019 (177) Apply 2019 filter

- 2018 (206) Apply 2018 filter

- 2017 (186) Apply 2017 filter

- 2016 (191) Apply 2016 filter

- 2015 (195) Apply 2015 filter

- 2014 (190) Apply 2014 filter

- 2013 (136) Apply 2013 filter

- 2012 (112) Apply 2012 filter

- 2011 (98) Apply 2011 filter

- 2010 (61) Apply 2010 filter

- 2009 (56) Apply 2009 filter

- 2008 (40) Apply 2008 filter

- 2007 (21) Apply 2007 filter

- 2006 (3) Apply 2006 filter

2809 Janelia Publications

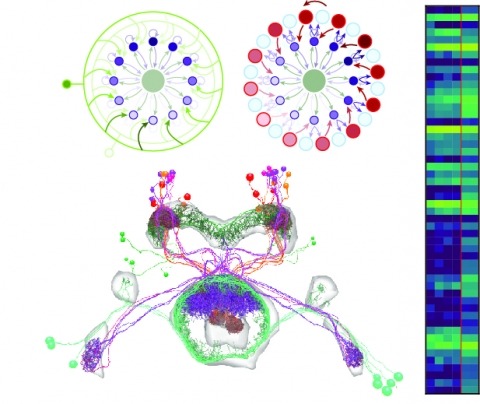

Showing 2541-2550 of 2809 resultsAnimal sounds are produced by patterned vibrations of specific organs, but the neural circuits that drive these vibrations are not well defined in any animal. Here we provide a functional and synaptic map of most of the neurons in the Drosophila male ventral nerve cord (the analog of the vertebrate spinal cord) that drive complex, patterned song during courtship. Male Drosophila vibrate their wings toward females during courtship to produce two distinct song modes – pulse and sine song – with characteristic features that signal species identity and male quality. We identified song-producing neural circuits by optogenetically activating and inhibiting identified cell types in the ventral nerve cord (VNC) and by tracing their patterns of synaptic connectivity in the male VNC connectome. The core song circuit consists of at least eight cell types organized into overlapping circuits, where all neurons are required for pulse song and a subset are required for sine song. The pulse and sine circuits each include a feed-forward pathway from brain descending neurons to wing motor neurons, with extensive reciprocal and feed-back connections. We also identify specific neurons that shape the individual features of each song mode. These results reveal commonalities amongst diverse animals in the neural mechanisms that generate diverse motor patterns from a single set of muscles.

The mammalian taste system is responsible for sensing and responding to the five basic taste qualities: sweet, sour, bitter, salty and umami. Previously, we showed that each taste is detected by dedicated taste receptor cells (TRCs) on the tongue and palate epithelium. To understand how TRCs transmit information to higher neural centres, we examined the tuning properties of large ensembles of neurons in the first neural station of the gustatory system. Here, we generated and characterized a collection of transgenic mice expressing a genetically encoded calcium indicator in central and peripheral neurons, and used a gradient refractive index microendoscope combined with high-resolution two-photon microscopy to image taste responses from ganglion neurons buried deep at the base of the brain. Our results reveal fine selectivity in the taste preference of ganglion neurons; demonstrate a strong match between TRCs in the tongue and the principal neural afferents relaying taste information to the brain; and expose the highly specific transfer of taste information between taste cells and the central nervous system.

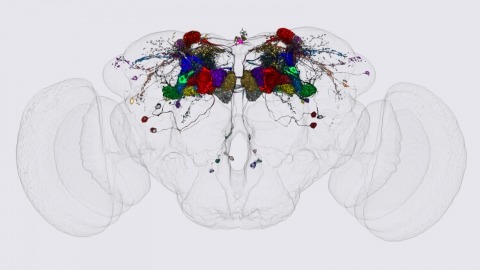

Neural representations of head direction (HD) have been discovered in many species. Theoretical work has proposed that the dynamics associated with these representations are generated, maintained, and updated by recurrent network structures called ring attractors. We evaluated this theorized structure-function relationship by performing electron-microscopy-based circuit reconstruction and RNA profiling of identified cell types in the HD system of Drosophila melanogaster. We identified motifs that have been hypothesized to maintain the HD representation in darkness, update it when the animal turns, and tether it to visual cues. Functional studies provided support for the proposed roles of individual excitatory or inhibitory circuit elements in shaping activity. We also discovered recurrent connections between neuronal arbors with mixed pre- and postsynaptic specializations. Our results confirm that the Drosophila HD network contains the core components of a ring attractor while also revealing unpredicted structural features that might enhance the network's computational power.

The neurophysiology of cells and tissues are monitored electrophysiologically and optically in diverse experiments and species, ranging from flies to humans. Understanding the brain requires integration of data across this diversity, and thus these data must be findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable (FAIR). This requires a standard language for data and metadata that can coevolve with neuroscience. We describe design and implementation principles for a language for neurophysiology data. Our open-source software (Neurodata Without Borders, NWB) defines and modularizes the interdependent, yet separable, components of a data language. We demonstrate NWB's impact through unified description of neurophysiology data across diverse modalities and species. NWB exists in an ecosystem, which includes data management, analysis, visualization, and archive tools. Thus, the NWB data language enables reproduction, interchange, and reuse of diverse neurophysiology data. More broadly, the design principles of NWB are generally applicable to enhance discovery across biology through data FAIRness.

We identified the neurons comprising the Drosophila mushroom body (MB), an associative center in invertebrate brains, and provide a comprehensive map describing their potential connections. Each of the 21 MB output neuron (MBON) types elaborates segregated dendritic arbors along the parallel axons of ∼2000 Kenyon cells, forming 15 compartments that collectively tile the MB lobes. MBON axons project to five discrete neuropils outside of the MB and three MBON types form a feedforward network in the lobes. Each of the 20 dopaminergic neuron (DAN) types projects axons to one, or at most two, of the MBON compartments. Convergence of DAN axons on compartmentalized Kenyon cell-MBON synapses creates a highly ordered unit that can support learning to impose valence on sensory representations. The elucidation of the complement of neurons of the MB provides a comprehensive anatomical substrate from which one can infer a functional logic of associative olfactory learning and memory.

Both vertebrates and invertebrates perceive illusory motion, known as "reverse-phi," in visual stimuli that contain sequential luminance increments and decrements. However, increment (ON) and decrement (OFF) signals are initially processed by separate visual neurons, and parallel elementary motion detectors downstream respond selectively to the motion of light or dark edges, often termed ON- and OFF-edges. It remains unknown how and where ON and OFF signals combine to generate reverse-phi motion signals. Here, we show that each of Drosophila's elementary motion detectors encodes motion by combining both ON and OFF signals. Their pattern of responses reflects combinations of increments and decrements that co-occur in natural motion, serving to decorrelate their outputs. These results suggest that the general principle of signal decorrelation drives the functional specialization of parallel motion detection channels, including their selectivity for moving light or dark edges.

Social isolation strongly modulates behavior across the animal kingdom. We utilized the fruit fly to study social isolation-driven changes in animal behavior and gene expression in the brain. RNA-seq identified several head-expressed genes strongly responding to social isolation or enrichment. Of particular interest, social isolation downregulated expression of the gene encoding the neuropeptide (), the homologue of vertebrate cholecystokinin (CCK), which is critical for many mammalian social behaviors. knockdown significantly increased social isolation-induced aggression. Genetic activation or silencing of neurons each similarly increased isolation-driven aggression. Our results suggest a U-shaped dependence of social isolation-induced aggressive behavior on signaling, similar to the actions of many neuromodulators in other contexts.

We review recent progress in neural probes for brain recording, with a focus on the Neuropixels platform. Historically the number of neurons’ recorded simultaneously, follows a Moore’s law like behavior, with numbers doubling every 6.7 years. Using traditional techniques of probe fabrication, continuing to scale up electrode densities is very challenging. We describe a custom CMOS process technology that enables electrode counts well beyond 1000 electrodes; with the aim to characterize large neural populations with single neuron spatial precision and millisecond timing resolution. This required integrating analog and digital circuitry with the electrode array, making it a standalone integrated electrophysiology recording system. Input referred noise and power per channel is 7.5µV and <50µW respectively to ensure tissue heating <1°C. This approach enables doubling the number of measured neurons every 12 months.

The coordination of growth with nutritional status is essential for proper development and physiology. Nutritional information is mostly perceived by peripheral organs before being relayed to the brain, which modulates physiological responses. Hormonal signaling ensures this organ-to-organ communication, and the failure of endocrine regulation in humans can cause diseases including obesity and diabetes. In Drosophila melanogaster, the fat body (adipose tissue) has been suggested to play an important role in coupling growth with nutritional status. Here, we show that the peripheral tissue-derived peptide hormone CCHamide-2 (CCHa2) acts as a nutrient-dependent regulator of Drosophila insulin-like peptides (Dilps). A BAC-based transgenic reporter revealed strong expression of CCHa2 receptor (CCHa2-R) in insulin-producing cells (IPCs) in the brain. Calcium imaging of brain explants and IPC-specific CCHa2-R knockdown demonstrated that peripheral-tissue derived CCHa2 directly activates IPCs. Interestingly, genetic disruption of either CCHa2 or CCHa2-R caused almost identical defects in larval growth and developmental timing. Consistent with these phenotypes, the expression of dilp5, and the release of both Dilp2 and Dilp5, were severely reduced. Furthermore, transcription of CCHa2 is altered in response to nutritional levels, particularly of glucose. These findings demonstrate that CCHa2 and CCHa2-R form a direct link between peripheral tissues and the brain, and that this pathway is essential for the coordination of systemic growth with nutritional availability. A mammalian homologue of CCHa2-R, Bombesin receptor subtype-3 (Brs3), is an orphan receptor that is expressed in the islet β-cells; however, the role of Brs3 in insulin regulation remains elusive. Our genetic approach in Drosophila melanogaster provides the first evidence, to our knowledge, that bombesin receptor signaling with its endogenous ligand promotes insulin production.