Filter

Associated Lab

- Aguilera Castrejon Lab (2) Apply Aguilera Castrejon Lab filter

- Ahrens Lab (61) Apply Ahrens Lab filter

- Aso Lab (42) Apply Aso Lab filter

- Baker Lab (19) Apply Baker Lab filter

- Betzig Lab (103) Apply Betzig Lab filter

- Beyene Lab (10) Apply Beyene Lab filter

- Bock Lab (14) Apply Bock Lab filter

- Branson Lab (51) Apply Branson Lab filter

- Card Lab (37) Apply Card Lab filter

- Cardona Lab (45) Apply Cardona Lab filter

- Chklovskii Lab (10) Apply Chklovskii Lab filter

- Clapham Lab (14) Apply Clapham Lab filter

- Cui Lab (19) Apply Cui Lab filter

- Darshan Lab (8) Apply Darshan Lab filter

- Dennis Lab (1) Apply Dennis Lab filter

- Dickson Lab (32) Apply Dickson Lab filter

- Druckmann Lab (21) Apply Druckmann Lab filter

- Dudman Lab (41) Apply Dudman Lab filter

- Eddy/Rivas Lab (30) Apply Eddy/Rivas Lab filter

- Egnor Lab (4) Apply Egnor Lab filter

- Espinosa Medina Lab (19) Apply Espinosa Medina Lab filter

- Feliciano Lab (12) Apply Feliciano Lab filter

- Fetter Lab (31) Apply Fetter Lab filter

- FIB-SEM Technology (1) Apply FIB-SEM Technology filter

- Fitzgerald Lab (16) Apply Fitzgerald Lab filter

- Freeman Lab (15) Apply Freeman Lab filter

- Funke Lab (42) Apply Funke Lab filter

- Gonen Lab (59) Apply Gonen Lab filter

- Grigorieff Lab (34) Apply Grigorieff Lab filter

- Harris Lab (55) Apply Harris Lab filter

- Heberlein Lab (13) Apply Heberlein Lab filter

- Hermundstad Lab (26) Apply Hermundstad Lab filter

- Hess Lab (76) Apply Hess Lab filter

- Ilanges Lab (3) Apply Ilanges Lab filter

- Jayaraman Lab (44) Apply Jayaraman Lab filter

- Ji Lab (33) Apply Ji Lab filter

- Johnson Lab (1) Apply Johnson Lab filter

- Karpova Lab (13) Apply Karpova Lab filter

- Keleman Lab (8) Apply Keleman Lab filter

- Keller Lab (61) Apply Keller Lab filter

- Koay Lab (3) Apply Koay Lab filter

- Lavis Lab (144) Apply Lavis Lab filter

- Lee (Albert) Lab (29) Apply Lee (Albert) Lab filter

- Leonardo Lab (19) Apply Leonardo Lab filter

- Li Lab (6) Apply Li Lab filter

- Lippincott-Schwartz Lab (108) Apply Lippincott-Schwartz Lab filter

- Liu (Yin) Lab (3) Apply Liu (Yin) Lab filter

- Liu (Zhe) Lab (59) Apply Liu (Zhe) Lab filter

- Looger Lab (137) Apply Looger Lab filter

- Magee Lab (31) Apply Magee Lab filter

- Menon Lab (12) Apply Menon Lab filter

- Murphy Lab (6) Apply Murphy Lab filter

- O'Shea Lab (6) Apply O'Shea Lab filter

- Otopalik Lab (1) Apply Otopalik Lab filter

- Pachitariu Lab (40) Apply Pachitariu Lab filter

- Pastalkova Lab (5) Apply Pastalkova Lab filter

- Pavlopoulos Lab (7) Apply Pavlopoulos Lab filter

- Pedram Lab (4) Apply Pedram Lab filter

- Podgorski Lab (16) Apply Podgorski Lab filter

- Reiser Lab (49) Apply Reiser Lab filter

- Riddiford Lab (20) Apply Riddiford Lab filter

- Romani Lab (39) Apply Romani Lab filter

- Rubin Lab (111) Apply Rubin Lab filter

- Saalfeld Lab (47) Apply Saalfeld Lab filter

- Satou Lab (3) Apply Satou Lab filter

- Scheffer Lab (38) Apply Scheffer Lab filter

- Schreiter Lab (53) Apply Schreiter Lab filter

- Sgro Lab (2) Apply Sgro Lab filter

- Shroff Lab (31) Apply Shroff Lab filter

- Simpson Lab (18) Apply Simpson Lab filter

- Singer Lab (37) Apply Singer Lab filter

- Spruston Lab (61) Apply Spruston Lab filter

- Stern Lab (75) Apply Stern Lab filter

- Sternson Lab (47) Apply Sternson Lab filter

- Stringer Lab (38) Apply Stringer Lab filter

- Svoboda Lab (132) Apply Svoboda Lab filter

- Tebo Lab (11) Apply Tebo Lab filter

- Tervo Lab (9) Apply Tervo Lab filter

- Tillberg Lab (19) Apply Tillberg Lab filter

- Tjian Lab (17) Apply Tjian Lab filter

- Truman Lab (58) Apply Truman Lab filter

- Turaga Lab (41) Apply Turaga Lab filter

- Turner Lab (27) Apply Turner Lab filter

- Vale Lab (8) Apply Vale Lab filter

- Voigts Lab (4) Apply Voigts Lab filter

- Wang (Meng) Lab (27) Apply Wang (Meng) Lab filter

- Wang (Shaohe) Lab (6) Apply Wang (Shaohe) Lab filter

- Wong-Campos Lab (1) Apply Wong-Campos Lab filter

- Wu Lab (8) Apply Wu Lab filter

- Zlatic Lab (26) Apply Zlatic Lab filter

- Zuker Lab (5) Apply Zuker Lab filter

Associated Project Team

- CellMap (12) Apply CellMap filter

- COSEM (3) Apply COSEM filter

- FIB-SEM Technology (5) Apply FIB-SEM Technology filter

- Fly Descending Interneuron (12) Apply Fly Descending Interneuron filter

- Fly Functional Connectome (14) Apply Fly Functional Connectome filter

- Fly Olympiad (5) Apply Fly Olympiad filter

- FlyEM (56) Apply FlyEM filter

- FlyLight (50) Apply FlyLight filter

- GENIE (47) Apply GENIE filter

- Integrative Imaging (9) Apply Integrative Imaging filter

- Larval Olympiad (2) Apply Larval Olympiad filter

- MouseLight (18) Apply MouseLight filter

- NeuroSeq (1) Apply NeuroSeq filter

- ThalamoSeq (1) Apply ThalamoSeq filter

- Tool Translation Team (T3) (29) Apply Tool Translation Team (T3) filter

- Transcription Imaging (45) Apply Transcription Imaging filter

Associated Support Team

- Project Pipeline Support (5) Apply Project Pipeline Support filter

- Anatomy and Histology (18) Apply Anatomy and Histology filter

- Cryo-Electron Microscopy (41) Apply Cryo-Electron Microscopy filter

- Electron Microscopy (18) Apply Electron Microscopy filter

- Gene Targeting and Transgenics (11) Apply Gene Targeting and Transgenics filter

- High Performance Computing (7) Apply High Performance Computing filter

- Integrative Imaging (18) Apply Integrative Imaging filter

- Invertebrate Shared Resource (40) Apply Invertebrate Shared Resource filter

- Janelia Experimental Technology (37) Apply Janelia Experimental Technology filter

- Management Team (1) Apply Management Team filter

- Mass Spectrometry (1) Apply Mass Spectrometry filter

- Molecular Genomics (15) Apply Molecular Genomics filter

- Project Technical Resources (54) Apply Project Technical Resources filter

- Quantitative Genomics (20) Apply Quantitative Genomics filter

- Scientific Computing (102) Apply Scientific Computing filter

- Stem Cell & Primary Culture (14) Apply Stem Cell & Primary Culture filter

- Viral Tools (14) Apply Viral Tools filter

- Vivarium (7) Apply Vivarium filter

Publication Date

- 2026 (27) Apply 2026 filter

- 2025 (224) Apply 2025 filter

- 2024 (211) Apply 2024 filter

- 2023 (157) Apply 2023 filter

- 2022 (166) Apply 2022 filter

- 2021 (175) Apply 2021 filter

- 2020 (177) Apply 2020 filter

- 2019 (177) Apply 2019 filter

- 2018 (206) Apply 2018 filter

- 2017 (186) Apply 2017 filter

- 2016 (191) Apply 2016 filter

- 2015 (195) Apply 2015 filter

- 2014 (190) Apply 2014 filter

- 2013 (136) Apply 2013 filter

- 2012 (112) Apply 2012 filter

- 2011 (98) Apply 2011 filter

- 2010 (61) Apply 2010 filter

- 2009 (56) Apply 2009 filter

- 2008 (40) Apply 2008 filter

- 2007 (21) Apply 2007 filter

- 2006 (3) Apply 2006 filter

2809 Janelia Publications

Showing 581-590 of 2809 resultsBACKGROUND: Unbiased screening studies have repeatedly identified actin-related proteins as one of the families of proteins most influenced by neurotrauma. Nevertheless, the status quo model of cytoskeletal reorganization after neurotrauma excludes actin and incorporates only changes in microtubules and intermediate filaments. Actin is excluded in part because it is difficult to image with conventional techniques. However, recent innovations in fluorescent microscopy provide an opportunity to image the actin cytoskeleton at super-resolution resolution in living cells. This study applied these innovations to an in vitro model of neurotrauma. NEW METHOD: New methods are introduced for traumatizing neurons before imaging them with high speed structured illumination microscopy or lattice light sheet microscopy. Also, methods for analyzing structured illumination microscopy images to quantify post-traumatic neurite dystrophy are presented. RESULTS: Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neurons exhibited actin organization typical of immature neurons. Neurite dystrophy increased after trauma but was not influenced by jasplakinolide treatment. The F-actin content of dystrophies varied greatly from one dystrophy to another. COMPARISON WITH EXISTING METHODS: In contrast to fixation dependent methods, these methods capture the evolution of the actin cytoskeleton over time in a living cell. In contrast to prior methods based on counting dystrophies, this quantification scheme parameterizes the severity of a given dystrophy as it evolves from a local swelling to an almost-perfect spheroid that threatens to transect the neurite. CONCLUSIONS: These methods can be used to investigate genetic factors and therapeutic interventions that modulate the course of neurite dystrophy after trauma.

Chemogenetics is a technique for obtaining selective pharmacological control over a cell population by expressing an engineered receptor that is selectively activated by an exogenously administered ligand. A promising approach for neuronal modulation involves the use of “Pharmacologically Selective Actuator Modules” (PSAMs); these chemogenetic receptors are selectively activated by ultrapotent “Pharmacologically Selective Effector Molecules” (uPSEMs). To extend the use of PSAM/PSEMs to studies in nonhuman primates it is necessary to thoroughly characterize the efficacy and safety of these tools. We describe the time course and brain penetrance in rhesus monkeys of two compounds with promising binding specificity and efficacy profiles in in vitro studies, uPSEM792 and uPSEM817, after systemic administration. Rhesus macaques received subcutaneous (s.c.) or intravenous (i.v.) administration of uPSEM817(0.064 mg/kg) or uPSEM792 (0.87 mg/kg) and plasma and CSF samples were collected over the course of 48 hours. Both compounds exhibited good brain penetrance, relatively slow washout and negligible conversion to potential metabolites - varenicline or hydroxyvarenicline. In addition, we found that neither of these uPSEMs significantly altered heart rate or sleep. Our results indicate that both compounds are suitable candidates for neuroscience studies using PSAMs in nonhuman primates.

Chemogenetics is a technique for obtaining selective pharmacological control over a cell population by expressing an engineered receptor that is selectively activated by an exogenously administered ligand. A promising approach for neuronal modulation involves the use of "Pharmacologically Selective Actuator Modules" (PSAMs); these chemogenetic receptors are selectively activated by ultrapotent "Pharmacologically Selective Effector Molecules" (uPSEMs). To extend the use of PSAM/PSEMs to studies in nonhuman primates, it is necessary to thoroughly characterize the efficacy and safety of these tools. We describe the time course and brain penetrance in rhesus monkeys of two compounds with promising binding specificity and efficacy profiles in studies, uPSEM792 and uPSEM817, after systemic administration. Rhesus monkeys received subcutaneous (s.c.) or intravenous (i.v.) administration of uPSEM817 (0.064 mg/kg) or uPSEM792 (0.87 mg/kg), and plasma and cerebrospinal fluid samples were collected over 48 h. Both compounds exhibited good brain penetrance, relatively slow washout, and negligible conversion to potential metabolites─varenicline or hydroxyvarenicline. In addition, we found that neither of these uPSEMs significantly altered the heart rate or sleep. Our results indicate that both compounds are suitable candidates for neuroscience studies using PSAMs in nonhuman primates.

Lattice light sheet microscopy excels at the non-invasive imaging of three-dimensional (3D) dynamic processes at high spatiotemporal resolution within cells and developing embryos. Recently, several papers have called into question the performance of lattice light sheets relative to the Gaussian sheets most common in light sheet microscopy. Here we undertake a comprehensive theoretical and experimental analysis of various forms of light sheet microscopy which both demonstrates and explains why lattice light sheets provide significant improvements in resolution and photobleaching reduction. The analysis provides a procedure to select the correct light sheet for a desired experiment and specifies the processing that maximizes the use of all fluorescence generated within the light sheet excitation envelope for optimal resolution while minimizing image artifacts and photodamage. Development of a new type of “harmonic balanced” lattice light sheet is shown to improve performance at all spatial frequencies within its 3D resolution limits and maintains this performance over lengthened propagation distances allowing for expanded fields of view.

To gain insights into coordinated lineage-specification and morphogenetic processes during early embryogenesis, here we report a systematic identification of transcriptional programs mediated by a key developmental regulator-Brachyury. High-resolution chromosomal localization mapping of Brachyury by ChIP sequencing and ChIP-exonuclease revealed distinct sequence signatures enriched in Brachyury-bound enhancers. A combination of genome-wide in vitro and in vivo perturbation analysis and cross-species evolutionary comparison unveiled a detailed Brachyury-dependent gene-regulatory network that directly links the function of Brachyury to diverse developmental pathways and cellular housekeeping programs. We also show that Brachyury functions primarily as a transcriptional activator genome-wide and that an unexpected gene-regulatory feedback loop consisting of Brachyury, Foxa2, and Sox17 directs proper stem-cell lineage commitment during streak formation. Target gene and mRNA-sequencing correlation analysis of the T(c) mouse model supports a crucial role of Brachyury in up-regulating multiple key hematopoietic and muscle-fate regulators. Our results thus chart a comprehensive map of the Brachyury-mediated gene-regulatory network and how it influences in vivo developmental homeostasis and coordination.

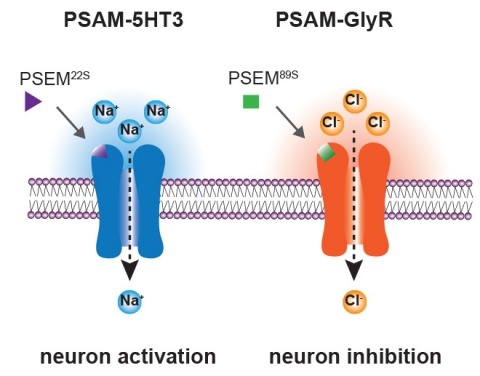

Ionic flux mediates essential physiological and behavioral functions in defined cell populations. Cell type-specific activators of diverse ionic conductances are needed for probing these effects. We combined chemistry and protein engineering to enable the systematic creation of a toolbox of ligand-gated ion channels (LGICs) with orthogonal pharmacologic selectivity and divergent functional properties. The LGICs and their small-molecule effectors were able to activate a range of ionic conductances in genetically specified cell types. LGICs constructed for neuronal perturbation could be used to selectively manipulate neuron activity in mammalian brains in vivo. The diversity of ion channel tools accessible from this approach will be useful for examining the relationship between neuronal activity and animal behavior, as well as for cell biological and physiological applications requiring chemical control of ion conductance.

Microbiota-derived metabolites have emerged as key regulators of longevity. The metabolic activity of the gut microbiota, influenced by dietary components and ingested chemical compounds, profoundly impacts host fitness. While the benefits of dietary prebiotics are well-known, chemically targeting the gut microbiota to enhance host fitness remains largely unexplored. Here, we report a novel chemical approach to induce a pro-longevity bacterial metabolite in the host gut. We discovered that specific Escherichia coli strains overproduce colanic acids (CAs) when exposed to a low dose of cephaloridine, leading to an increased lifespan in host Caenorhabditis elegans. In the mouse gut, oral administration of low-dose cephaloridine induces the transcription of the capsular biosynthesis operon responsible for CA biosynthesis in commensal E. coli, which overcomes the inhibition of CA biosynthesis above 30 degrees C and enables its induction directly from the microbiota. Importantly, low-dose cephaloridine induces CA independently of its antibiotic properties through a previously unknown mechanism mediated by the membrane-bound histidine kinase ZraS. Our work lays the foundation for microbiota-based therapeutics through the chemical modulation of bacterial metabolism and reveals the promising potential of bacteria-targeting drugs in promoting host longevity.

Microbiota-derived metabolites have emerged as key regulators of longevity. The metabolic activity of the gut microbiota, influenced by dietary components and ingested chemical compounds, profoundly impacts host fitness. While the benefits of dietary prebiotics are well-known, chemically targeting the gut microbiota to enhance host fitness remains largely unexplored. Here, we report a novel chemical approach to induce a pro-longevity bacterial metabolite in the host gut. We discovered that wild-type Escherichia coli strains overproduce colanic acids (CAs) when exposed to a low dose of cephaloridine, leading to an increased life span in the host organism Caenorhabditis elegans. In the mouse gut, oral administration of low-dose cephaloridine induced transcription of the capsular polysaccharide synthesis (cps) operon responsible for CA biosynthesis in commensal E. coli at 37 °C, and attenuated age-related metabolic changes. We also found that low-dose cephaloridine overcomes the temperature-dependent inhibition of CA biosynthesis and promotes its induction through a mechanism mediated by the membrane-bound histidine kinase ZraS, independently of cephaloridine's known antibiotic properties. Our work lays a foundation for microbiota-based therapeutics through chemical modulation of bacterial metabolism and highlights the promising potential of leveraging bacteria-targeting drugs in promoting host longevity.

Intrinsically disordered protein regions (IDRs) are peptide segments that fail to form stable 3-dimensional structures in the absence of partner proteins. They are abundant in eukaryotic proteomes and are often associated with human diseases, but their biological functions have been elusive to study. Here we report the identification of a tin(IV) oxochloride-derived cluster that binds an evolutionarily conserved IDR within the metazoan TFIID transcription complex. Binding arrests an isomerization of promoter-bound TFIID that is required for the engagement of Pol II during the first (de novo) round of transcription initiation. However, the specific chemical probe does not affect reinitiation, which requires the re-entry of Pol II, thus, mechanistically distinguishing these two modes of transcription initiation. This work also suggests a new avenue for targeting the elusive IDRs by harnessing certain features of metal-based complexes for mechanistic studies, and for the development of novel pharmaceutical interventions.