Filter

Associated Lab

- Aguilera Castrejon Lab (17) Apply Aguilera Castrejon Lab filter

- Ahrens Lab (68) Apply Ahrens Lab filter

- Aso Lab (42) Apply Aso Lab filter

- Baker Lab (38) Apply Baker Lab filter

- Betzig Lab (115) Apply Betzig Lab filter

- Beyene Lab (14) Apply Beyene Lab filter

- Bock Lab (17) Apply Bock Lab filter

- Branson Lab (54) Apply Branson Lab filter

- Card Lab (43) Apply Card Lab filter

- Cardona Lab (64) Apply Cardona Lab filter

- Chklovskii Lab (13) Apply Chklovskii Lab filter

- Clapham Lab (15) Apply Clapham Lab filter

- Cui Lab (19) Apply Cui Lab filter

- Darshan Lab (12) Apply Darshan Lab filter

- Dennis Lab (1) Apply Dennis Lab filter

- Dickson Lab (46) Apply Dickson Lab filter

- Druckmann Lab (25) Apply Druckmann Lab filter

- Dudman Lab (52) Apply Dudman Lab filter

- Eddy/Rivas Lab (30) Apply Eddy/Rivas Lab filter

- Egnor Lab (11) Apply Egnor Lab filter

- Espinosa Medina Lab (21) Apply Espinosa Medina Lab filter

- Feliciano Lab (10) Apply Feliciano Lab filter

- Fetter Lab (41) Apply Fetter Lab filter

- FIB-SEM Technology (1) Apply FIB-SEM Technology filter

- Fitzgerald Lab (29) Apply Fitzgerald Lab filter

- Freeman Lab (15) Apply Freeman Lab filter

- Funke Lab (41) Apply Funke Lab filter

- Gonen Lab (91) Apply Gonen Lab filter

- Grigorieff Lab (62) Apply Grigorieff Lab filter

- Harris Lab (64) Apply Harris Lab filter

- Heberlein Lab (94) Apply Heberlein Lab filter

- Hermundstad Lab (29) Apply Hermundstad Lab filter

- Hess Lab (79) Apply Hess Lab filter

- Ilanges Lab (2) Apply Ilanges Lab filter

- Jayaraman Lab (47) Apply Jayaraman Lab filter

- Ji Lab (33) Apply Ji Lab filter

- Johnson Lab (6) Apply Johnson Lab filter

- Kainmueller Lab (19) Apply Kainmueller Lab filter

- Karpova Lab (14) Apply Karpova Lab filter

- Keleman Lab (13) Apply Keleman Lab filter

- Keller Lab (76) Apply Keller Lab filter

- Koay Lab (18) Apply Koay Lab filter

- Lavis Lab (154) Apply Lavis Lab filter

- Lee (Albert) Lab (34) Apply Lee (Albert) Lab filter

- Leonardo Lab (23) Apply Leonardo Lab filter

- Li Lab (30) Apply Li Lab filter

- Lippincott-Schwartz Lab (178) Apply Lippincott-Schwartz Lab filter

- Liu (Yin) Lab (7) Apply Liu (Yin) Lab filter

- Liu (Zhe) Lab (64) Apply Liu (Zhe) Lab filter

- Looger Lab (138) Apply Looger Lab filter

- Magee Lab (49) Apply Magee Lab filter

- Menon Lab (18) Apply Menon Lab filter

- Murphy Lab (13) Apply Murphy Lab filter

- O'Shea Lab (7) Apply O'Shea Lab filter

- Otopalik Lab (13) Apply Otopalik Lab filter

- Pachitariu Lab (49) Apply Pachitariu Lab filter

- Pastalkova Lab (18) Apply Pastalkova Lab filter

- Pavlopoulos Lab (19) Apply Pavlopoulos Lab filter

- Pedram Lab (15) Apply Pedram Lab filter

- Podgorski Lab (16) Apply Podgorski Lab filter

- Reiser Lab (53) Apply Reiser Lab filter

- Riddiford Lab (44) Apply Riddiford Lab filter

- Romani Lab (48) Apply Romani Lab filter

- Rubin Lab (147) Apply Rubin Lab filter

- Saalfeld Lab (64) Apply Saalfeld Lab filter

- Satou Lab (16) Apply Satou Lab filter

- Scheffer Lab (38) Apply Scheffer Lab filter

- Schreiter Lab (68) Apply Schreiter Lab filter

- Sgro Lab (21) Apply Sgro Lab filter

- Shroff Lab (31) Apply Shroff Lab filter

- Simpson Lab (23) Apply Simpson Lab filter

- Singer Lab (80) Apply Singer Lab filter

- Spruston Lab (97) Apply Spruston Lab filter

- Stern Lab (158) Apply Stern Lab filter

- Sternson Lab (54) Apply Sternson Lab filter

- Stringer Lab (39) Apply Stringer Lab filter

- Svoboda Lab (135) Apply Svoboda Lab filter

- Tebo Lab (35) Apply Tebo Lab filter

- Tervo Lab (9) Apply Tervo Lab filter

- Tillberg Lab (21) Apply Tillberg Lab filter

- Tjian Lab (64) Apply Tjian Lab filter

- Truman Lab (88) Apply Truman Lab filter

- Turaga Lab (53) Apply Turaga Lab filter

- Turner Lab (39) Apply Turner Lab filter

- Vale Lab (8) Apply Vale Lab filter

- Voigts Lab (3) Apply Voigts Lab filter

- Wang (Meng) Lab (27) Apply Wang (Meng) Lab filter

- Wang (Shaohe) Lab (25) Apply Wang (Shaohe) Lab filter

- Wu Lab (9) Apply Wu Lab filter

- Zlatic Lab (28) Apply Zlatic Lab filter

- Zuker Lab (25) Apply Zuker Lab filter

Associated Project Team

- CellMap (12) Apply CellMap filter

- COSEM (3) Apply COSEM filter

- FIB-SEM Technology (5) Apply FIB-SEM Technology filter

- Fly Descending Interneuron (12) Apply Fly Descending Interneuron filter

- Fly Functional Connectome (14) Apply Fly Functional Connectome filter

- Fly Olympiad (5) Apply Fly Olympiad filter

- FlyEM (56) Apply FlyEM filter

- FlyLight (50) Apply FlyLight filter

- GENIE (47) Apply GENIE filter

- Integrative Imaging (7) Apply Integrative Imaging filter

- Larval Olympiad (2) Apply Larval Olympiad filter

- MouseLight (18) Apply MouseLight filter

- NeuroSeq (1) Apply NeuroSeq filter

- ThalamoSeq (1) Apply ThalamoSeq filter

- Tool Translation Team (T3) (28) Apply Tool Translation Team (T3) filter

- Transcription Imaging (49) Apply Transcription Imaging filter

Publication Date

- 2025 (215) Apply 2025 filter

- 2024 (212) Apply 2024 filter

- 2023 (158) Apply 2023 filter

- 2022 (192) Apply 2022 filter

- 2021 (194) Apply 2021 filter

- 2020 (196) Apply 2020 filter

- 2019 (202) Apply 2019 filter

- 2018 (232) Apply 2018 filter

- 2017 (217) Apply 2017 filter

- 2016 (209) Apply 2016 filter

- 2015 (252) Apply 2015 filter

- 2014 (236) Apply 2014 filter

- 2013 (194) Apply 2013 filter

- 2012 (190) Apply 2012 filter

- 2011 (190) Apply 2011 filter

- 2010 (161) Apply 2010 filter

- 2009 (158) Apply 2009 filter

- 2008 (140) Apply 2008 filter

- 2007 (106) Apply 2007 filter

- 2006 (92) Apply 2006 filter

- 2005 (67) Apply 2005 filter

- 2004 (57) Apply 2004 filter

- 2003 (58) Apply 2003 filter

- 2002 (39) Apply 2002 filter

- 2001 (28) Apply 2001 filter

- 2000 (29) Apply 2000 filter

- 1999 (14) Apply 1999 filter

- 1998 (18) Apply 1998 filter

- 1997 (16) Apply 1997 filter

- 1996 (10) Apply 1996 filter

- 1995 (18) Apply 1995 filter

- 1994 (12) Apply 1994 filter

- 1993 (10) Apply 1993 filter

- 1992 (6) Apply 1992 filter

- 1991 (11) Apply 1991 filter

- 1990 (11) Apply 1990 filter

- 1989 (6) Apply 1989 filter

- 1988 (1) Apply 1988 filter

- 1987 (7) Apply 1987 filter

- 1986 (4) Apply 1986 filter

- 1985 (5) Apply 1985 filter

- 1984 (2) Apply 1984 filter

- 1983 (2) Apply 1983 filter

- 1982 (3) Apply 1982 filter

- 1981 (3) Apply 1981 filter

- 1980 (1) Apply 1980 filter

- 1979 (1) Apply 1979 filter

- 1976 (2) Apply 1976 filter

- 1973 (1) Apply 1973 filter

- 1970 (1) Apply 1970 filter

- 1967 (1) Apply 1967 filter

Type of Publication

4190 Publications

Showing 2171-2180 of 4190 resultsInterplay between models and experimental data advances discovery and understanding in biology, particularly when models generate predictions that allow well-designed experiments to distinguish between alternative mechanisms. To illustrate how this feedback between models and experiments can lead to key insights into biological mechanisms, we explore three examples from cellular slime mold chemotaxis. These examples include studies that identified chemotaxis as the primary mechanism behind slime mold aggregation, discovered that cells likely measure chemoattractant gradients by sensing concentration differences across cell length, and tested the role of cell-associated chemoattractant degradation in shaping chemotactic fields. Although each study used a different model class appropriate to their hypotheses - qualitative, mathematical, or simulation-based - these examples all highlight the utility of modeling to formalize assumptions and generate testable predictions. A central element of this framework is the iterative use of models and experiments, specifically: matching experimental designs to the models, revising models based on mismatches with experimental data, and validating critical model assumptions and predictions with experiments. We advocate for continued use of this interplay between models and experiments to advance biological discovery.

A crystal structure of the anaerobic Ni-Fe-S carbon monoxide dehydrogenase (CODH) from Rhodospirillum rubrum has been determined to 2.8-Å resolution. The CODH family, for which the R. rubrum enzyme is the prototype, catalyzes the biological oxidation of CO at an unusual Ni-Fe-S cluster called the C-cluster. The Ni-Fe-S C-cluster contains a mononuclear site and a four-metal cubane. Surprisingly, anomalous dispersion data suggest that the mononuclear site contains Fe and not Ni, and the four-metal cubane has the form [NiFe3S4] and not [Fe4S4]. The mononuclear site and the four-metal cluster are bridged by means of Cys531 and one of the sulfides of the cube. CODH is organized as a dimer with a previously unidentified [Fe4S4] cluster bridging the two subunits. Each monomer is comprised of three domains: a helical domain at the N terminus, an α/β (Rossmann-like) domain in the middle, and an α/β (Rossmann-like) domain at the C terminus. The helical domain contributes ligands to the bridging [Fe4S4] cluster and another [Fe4S4] cluster, the B-cluster, which is involved in electron transfer. The two Rossmann domains contribute ligands to the active site C-cluster. This x-ray structure provides insight into the mechanism of biological CO oxidation and has broader significance for the roles of Ni and Fe in biological systems.

Novel technologies are required for three-dimensional cell biology and biophysics. By three-dimensional we refer to experimental conditions that essentially try to avoid hard and flat surfaces and favour unconstrained sample dynamics. We believe that light-sheet-based microscopes are particularly well suited to studies of sensitive three-dimensional biological systems. The application of such instruments can be illustrated with examples from the biophysics of microtubule dynamics and three-dimensional cell cultures. Our experience leads us to suggest that three-dimensional approaches reveal new aspects of a system and enable experiments to be performed in a more physiological and hence clinically more relevant context.

Light sheet fluorescence microscopy (LSFM) uses a thin sheet of light to excite only fluorophores within the focal volume. Light sheet microscopes (LSMs) have a true optical sectioning capability and, hence, provide axial resolution, restrict photobleaching and phototoxicity to a fraction of the sample and use cameras to record tens to thousands of images per second. LSMs are used for in-depth analyses of large, optically cleared samples and long-term three-dimensional (3D) observations of live biological specimens at high spatio-temporal resolution. The independently operated illumination and detection trains and the canonical implementations, selective/single plane illumination microscope (SPIM) and digital scanned laser microscope (DSLM), are the basis for many LSM designs. In this Primer, we discuss various applications of LSFM for imaging multicellular specimens, developing vertebrate and invertebrate embryos, brain and heart function, 3D cell culture models, single cells, tissue sections, plants, organismic interaction and entire cleared brains. Further, we describe the combination of LSFM with other imaging approaches to allow for super-resolution or increased penetration depth and the use of sophisticated spatio-temporal manipulations to allow for observations along multiple directions. Finally, we anticipate developments of the field in the near future.

Capturing dynamic processes in live samples is a nontrivial task in biological imaging. Although fluorescence provides high specificity and contrast compared to other light microscopy techniques, the photophysical principles of this method can have a harmful effect on the sample. Current advances in light sheet microscopy have created a novel imaging toolbox that allows for rapid acquisition of high-resolution fluorescent images with minimal perturbation of the processes of interest. Each unique design has its own advantages and limitations. In this review, we describe several cutting edge light sheet microscopes and their optimal applications.

Light sheet-based fluorescence microscopy (LSFM) is emerging as a powerful imaging technique for the life sciences. LSFM provides an exceptionally high imaging speed, high signal-to-noise ratio, low level of photo-bleaching, and good optical penetration depth. This unique combination of capabilities makes light sheet-based microscopes highly suitable for live imaging applications. Here, we provide an overview of light sheet-based microscopy assays for in vitro and in vivo imaging of biological samples, including cell extracts, soft gels, and large multicellular organisms. We furthermore describe computational tools for basic image processing and data inspection.

Light sheet microscopy is a versatile imaging technique with a unique combination of capabilities. It provides high imaging speed, high signal-to-noise ratio and low levels of photobleaching and phototoxic effects. These properties are crucial in a wide range of applications in the life sciences, from live imaging of fast dynamic processes in single cells to long-term observation of developmental dynamics in entire large organisms. When combined with tissue clearing methods, light sheet microscopy furthermore allows rapid imaging of large specimens with excellent coverage and high spatial resolution. Even samples up to the size of entire mammalian brains can be efficiently recorded and quantitatively analyzed. Here, we provide an overview of the history of light sheet microscopy, review the development of tissue clearing methods, and discuss recent technical breakthroughs that have the potential to influence the future direction of the field.

The fruit fly is an excellent model system for investigating the sequence of epithelial tissue invaginations constituting the process of gastrulation. By combining recent advancements in light sheet fluorescence microscopy (LSFM) and image processing, the three-dimensional fly embryo morphology and relevant gene expression patterns can be accurately recorded throughout the entire process of embryogenesis. LSFM provides exceptionally high imaging speed, high signal-to-noise ratio, low level of photoinduced damage, and good optical penetration depth. This powerful combination of capabilities makes LSFM particularly suitable for live imaging of the fly embryo.The resulting high-information-content image data are subsequently processed to obtain the outlines of cells and cell nuclei, as well as the geometry of the whole embryo tissue by image segmentation. Furthermore, morphodynamics information is extracted by computationally tracking objects in the image. Towards that goal we describe the successful implementation of a fast fitting strategy of Gaussian mixture models.The data obtained by image processing is well-suited for hypothesis testing of the detailed biomechanics of the gastrulating embryo. Typically this involves constructing computational mechanics models that consist of an objective function providing an estimate of strain energy for a given morphological configuration of the tissue, and a numerical minimization mechanism of this energy, achieved by varying morphological parameters.In this chapter, we provide an overview of in vivo imaging of fruit fly embryos using LSFM, computational tools suitable for processing the resulting images, and examples of computational biomechanical simulations of fly embryo gastrulation.

Photoreceptors for visual perception, phototaxis or light avoidance are typically clustered in eyes or related structures such as the Bolwig organ of Drosophila larvae. Unexpectedly, we found that the class IV dendritic arborization neurons of Drosophila melanogaster larvae respond to ultraviolet, violet and blue light, and are major mediators of light avoidance, particularly at high intensities. These class IV dendritic arborization neurons, which are present in every body segment, have dendrites tiling the larval body wall nearly completely without redundancy. Dendritic illumination activates class IV dendritic arborization neurons. These novel photoreceptors use phototransduction machinery distinct from other photoreceptors in Drosophila and enable larvae to sense light exposure over their entire bodies and move out of danger.

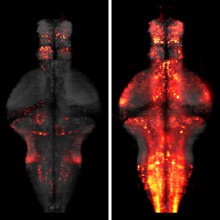

The processing of sensory input and the generation of behavior involves large networks of neurons, which necessitates new technology for recording from many neurons in behaving animals. In the larval zebrafish, light-sheet microscopy can be used to record the activity of almost all neurons in the brain simultaneously at single-cell resolution. Existing implementations, however, cannot be combined with visually driven behavior because the light sheet scans over the eye, interfering with presentation of controlled visual stimuli. Here we describe a system that overcomes the confounding eye stimulation through the use of two light sheets and combines whole-brain light-sheet imaging with virtual reality for fictively behaving larval zebrafish.