Filter

Associated Lab

- Aso Lab (30) Apply Aso Lab filter

- Betzig Lab (1) Apply Betzig Lab filter

- Bock Lab (2) Apply Bock Lab filter

- Branson Lab (8) Apply Branson Lab filter

- Card Lab (5) Apply Card Lab filter

- Clapham Lab (1) Apply Clapham Lab filter

- Dickson Lab (2) Apply Dickson Lab filter

- Druckmann Lab (1) Apply Druckmann Lab filter

- Fetter Lab (1) Apply Fetter Lab filter

- Funke Lab (1) Apply Funke Lab filter

- Harris Lab (3) Apply Harris Lab filter

- Heberlein Lab (2) Apply Heberlein Lab filter

- Hermundstad Lab (2) Apply Hermundstad Lab filter

- Hess Lab (5) Apply Hess Lab filter

- Jayaraman Lab (6) Apply Jayaraman Lab filter

- Lippincott-Schwartz Lab (1) Apply Lippincott-Schwartz Lab filter

- Looger Lab (2) Apply Looger Lab filter

- O'Shea Lab (1) Apply O'Shea Lab filter

- Otopalik Lab (1) Apply Otopalik Lab filter

- Reiser Lab (15) Apply Reiser Lab filter

- Riddiford Lab (1) Apply Riddiford Lab filter

- Romani Lab (1) Apply Romani Lab filter

- Rubin Lab (143) Apply Rubin Lab filter

- Saalfeld Lab (4) Apply Saalfeld Lab filter

- Scheffer Lab (7) Apply Scheffer Lab filter

- Schreiter Lab (1) Apply Schreiter Lab filter

- Simpson Lab (3) Apply Simpson Lab filter

- Singer Lab (1) Apply Singer Lab filter

- Spruston Lab (1) Apply Spruston Lab filter

- Stern Lab (1) Apply Stern Lab filter

- Svoboda Lab (3) Apply Svoboda Lab filter

- Tjian Lab (1) Apply Tjian Lab filter

- Truman Lab (4) Apply Truman Lab filter

- Turaga Lab (1) Apply Turaga Lab filter

- Turner Lab (5) Apply Turner Lab filter

- Zuker Lab (1) Apply Zuker Lab filter

Associated Project Team

- CellMap (1) Apply CellMap filter

- Fly Functional Connectome (4) Apply Fly Functional Connectome filter

- Fly Olympiad (3) Apply Fly Olympiad filter

- FlyEM (11) Apply FlyEM filter

- FlyLight (20) Apply FlyLight filter

- GENIE (1) Apply GENIE filter

- Transcription Imaging (1) Apply Transcription Imaging filter

Publication Date

- 2025 (4) Apply 2025 filter

- 2024 (4) Apply 2024 filter

- 2023 (5) Apply 2023 filter

- 2022 (1) Apply 2022 filter

- 2021 (4) Apply 2021 filter

- 2020 (9) Apply 2020 filter

- 2019 (6) Apply 2019 filter

- 2018 (7) Apply 2018 filter

- 2017 (15) Apply 2017 filter

- 2016 (3) Apply 2016 filter

- 2015 (16) Apply 2015 filter

- 2014 (9) Apply 2014 filter

- 2013 (5) Apply 2013 filter

- 2012 (8) Apply 2012 filter

- 2011 (4) Apply 2011 filter

- 2010 (4) Apply 2010 filter

- 2009 (2) Apply 2009 filter

- 2008 (4) Apply 2008 filter

- 2007 (2) Apply 2007 filter

- 2006 (1) Apply 2006 filter

- 2002 (1) Apply 2002 filter

- 2000 (2) Apply 2000 filter

- 1999 (1) Apply 1999 filter

- 1997 (1) Apply 1997 filter

- 1995 (2) Apply 1995 filter

- 1994 (2) Apply 1994 filter

- 1993 (2) Apply 1993 filter

- 1992 (1) Apply 1992 filter

- 1991 (2) Apply 1991 filter

- 1990 (3) Apply 1990 filter

- 1989 (2) Apply 1989 filter

- 1987 (2) Apply 1987 filter

- 1986 (1) Apply 1986 filter

- 1985 (1) Apply 1985 filter

- 1984 (1) Apply 1984 filter

- 1983 (1) Apply 1983 filter

- 1982 (2) Apply 1982 filter

- 1981 (1) Apply 1981 filter

- 1979 (1) Apply 1979 filter

- 1973 (1) Apply 1973 filter

Type of Publication

143 Publications

Showing 1-10 of 143 resultsDiffuse neuromodulatory systems such as norepinephrine (NE) control brain-wide states such as arousal, but whether they control complex social behaviors more specifically is not clear. Octopamine (OA), the insect homolog of NE, is known to promote both arousal and aggression. We have performed a systematic, unbiased screen to identify OA receptor-expressing neurons (OARNs) that control aggression in Drosophila. Our results uncover a tiny population of male-specific aSP2 neurons that mediate a specific influence of OA on aggression, independent of any effect on arousal. Unexpectedly, these neurons receive convergent input from OA neurons and P1 neurons, a population of FruM(+) neurons that promotes male courtship behavior. Behavioral epistasis experiments suggest that aSP2 neurons may constitute an integration node at which OAergic neuromodulation can bias the output of P1 neurons to favor aggression over inter-male courtship. These results have potential implications for thinking about the role of related neuromodulatory systems in mammals.

The neural circuits responsible for animal behavior remain largely unknown. We summarize new methods and present the circuitry of a large fraction of the brain of the fruit fly . Improved methods include new procedures to prepare, image, align, segment, find synapses in, and proofread such large data sets. We define cell types, refine computational compartments, and provide an exhaustive atlas of cell examples and types, many of them novel. We provide detailed circuits consisting of neurons and their chemical synapses for most of the central brain. We make the data public and simplify access, reducing the effort needed to answer circuit questions, and provide procedures linking the neurons defined by our analysis with genetic reagents. Biologically, we examine distributions of connection strengths, neural motifs on different scales, electrical consequences of compartmentalization, and evidence that maximizing packing density is an important criterion in the evolution of the fly's brain.

Understanding memory formation, storage and retrieval requires knowledge of the underlying neuronal circuits. In Drosophila, the mushroom body (MB) is the major site of associative learning. We reconstructed the morphologies and synaptic connections of all 983 neurons within the three functional units, or compartments, that compose the adult MB’s α lobe, using a dataset of isotropic 8-nm voxels collected by focused ion-beam milling scanning electron microscopy. We found that Kenyon cells (KCs), whose sparse activity encodes sensory information, each make multiple en passant synapses to MB output neurons (MBONs) in each compartment. Some MBONs have inputs from all KCs, while others differentially sample sensory modalities. Only six percent of KC>MBON synapses receive a direct synapse from a dopaminergic neuron (DAN). We identified two unanticipated classes of synapses, KC>DAN and DAN>MBON. DAN activation produces a slow depolarization of the MBON in these DAN>MBON synapses and can weaken memory recall.

Flexible behaviors over long timescales are thought to engage recurrent neural networks in deep brain regions, which are experimentally challenging to study. In insects, recurrent circuit dynamics in a brain region called the central complex (CX) enable directed locomotion, sleep, and context- and experience-dependent spatial navigation. We describe the first complete electron-microscopy-based connectome of the CX, including all its neurons and circuits at synaptic resolution. We identified new CX neuron types, novel sensory and motor pathways, and network motifs that likely enable the CX to extract the fly's head-direction, maintain it with attractor dynamics, and combine it with other sensorimotor information to perform vector-based navigational computations. We also identified numerous pathways that may facilitate the selection of CX-driven behavioral patterns by context and internal state. The CX connectome provides a comprehensive blueprint necessary for a detailed understanding of network dynamics underlying sleep, flexible navigation, and state-dependent action selection.

Animal behavior is principally expressed through neural control of muscles. Therefore understanding how the brain controls behavior requires mapping neuronal circuits all the way to motor neurons. We have previously established technology to collect large-volume electron microscopy data sets of neural tissue and fully reconstruct the morphology of the neurons and their chemical synaptic connections throughout the volume. Using these tools we generated a dense wiring diagram, or connectome, for a large portion of the Drosophila central brain. However, in most animals, including the fly, the majority of motor neurons are located outside the brain in a neural center closer to the body, i.e. the mammalian spinal cord or insect ventral nerve cord (VNC). In this paper, we extend our effort to map full neural circuits for behavior by generating a connectome of the VNC of a male fly.

The extraction of directional motion information from changing retinal images is one of the earliest and most important processing steps in any visual system. In the fly optic lobe, two parallel processing streams have been anatomically described, leading from two first-order interneurons, L1 and L2, via T4 and T5 cells onto large, wide-field motion-sensitive interneurons of the lobula plate. Therefore, T4 and T5 cells are thought to have a pivotal role in motion processing; however, owing to their small size, it is difficult to obtain electrical recordings of T4 and T5 cells, leaving their visual response properties largely unknown. We circumvent this problem by means of optical recording from these cells in Drosophila, using the genetically encoded calcium indicator GCaMP5 (ref. 2). Here we find that specific subpopulations of T4 and T5 cells are directionally tuned to one of the four cardinal directions; that is, front-to-back, back-to-front, upwards and downwards. Depending on their preferred direction, T4 and T5 cells terminate in specific sublayers of the lobula plate. T4 and T5 functionally segregate with respect to contrast polarity: whereas T4 cells selectively respond to moving brightness increments (ON edges), T5 cells only respond to moving brightness decrements (OFF edges). When the output from T4 or T5 cells is blocked, the responses of postsynaptic lobula plate neurons to moving ON (T4 block) or OFF edges (T5 block) are selectively compromised. The same effects are seen in turning responses of tethered walking flies. Thus, starting with L1 and L2, the visual input is split into separate ON and OFF pathways, and motion along all four cardinal directions is computed separately within each pathway. The output of these eight different motion detectors is then sorted such that ON (T4) and OFF (T5) motion detectors with the same directional tuning converge in the same layer of the lobula plate, jointly providing the input to downstream circuits and motion-driven behaviours.

Taste memories allow animals to modulate feeding behavior in accordance with past experience and avoid the consumption of potentially harmful food [1]. We have developed a single-fly taste memory assay to functionally interrogate the neural circuitry encoding taste memories [2]. Here, we screen a collection of Split-GAL4 lines that label small populations of neurons associated with the fly memory center-the mushroom bodies (MBs) [3]. Genetic silencing of PPL1 dopamine neurons disrupts conditioned, but not naive, feeding behavior, suggesting these neurons are selectively involved in the conditioned taste response. We identify two PPL1 subpopulations that innervate the MB α lobe and are essential for aversive taste memory. Thermogenetic activation of these dopamine neurons during training induces memory, indicating these neurons are sufficient for the reinforcing properties of bitter tastant to the MBs. Silencing of either the intrinsic MB neurons or the output neurons from the α lobe disrupts taste conditioning. Thermogenetic manipulation of these output neurons alters naive feeding response, suggesting that dopamine neurons modulate the threshold of response to appetitive tastants. Taken together, these findings detail a neural mechanism underlying the formation of taste memory and provide a functional model for dopamine-dependent plasticity in Drosophila.

Conditional expression of hairpin constructs in Drosophila is a powerful method to disrupt the activity of single genes with a spatial and temporal resolution that is impossible, or exceedingly difficult, using classical genetic methods. We previously described a method (Ni et al. 2008) whereby RNAi constructs are targeted into the genome by the phiC31-mediated integration approach using Vermilion-AttB-Loxp-Intron-UAS-MCS (VALIUM), a vector that contains vermilion as a selectable marker, an attB sequence to allow for phiC31-targeted integration at genomic attP landing sites, two pentamers of UAS, the hsp70 core promoter, a multiple cloning site, and two introns. As the level of gene activity knockdown associated with transgenic RNAi depends on the level of expression of the hairpin constructs, we generated a number of derivatives of our initial vector, called the "VALIUM" series, to improve the efficiency of the method. Here, we report the results from the systematic analysis of these derivatives and characterize VALIUM10 as the most optimal vector of this series. A critical feature of VALIUM10 is the presence of gypsy insulator sequences that boost dramatically the level of knockdown. We document the efficacy of VALIUM as a vector to analyze the phenotype of genes expressed in the nervous system and have generated a library of 2282 constructs targeting 2043 genes that will be particularly useful for studies of the nervous system as they target, in particular, transcription factors, ion channels, and transporters.

Topographic maps, the systematic spatial ordering of neurons by response tuning, are common across species. In Drosophila, the lobula columnar (LC) neuron types project from the optic lobe to the central brain, where each forms a glomerulus in a distinct position. However, the advantages of this glomerular arrangement are unclear. Here, we examine the functional and spatial relationships of 10 glomeruli using single-neuron calcium imaging. We discover novel detectors for objects smaller than the lens resolution (LC18) and for complex line motion (LC25). We find that glomeruli are spatially clustered by selectivity for looming versus drifting object motion and ordered by size tuning to form a topographic visual feature map. Furthermore, connectome analysis shows that downstream neurons integrate from sparse subsets of possible glomeruli combinations, which are biased for glomeruli encoding similar features. LC neurons are thus an explicit example of distinct feature detectors topographically organized to facilitate downstream circuit integration.

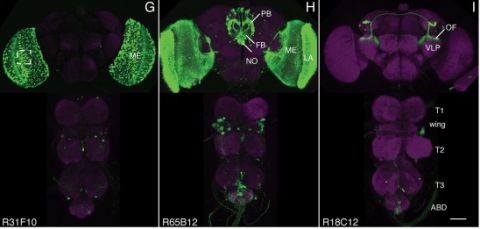

We established a collection of 7,000 transgenic lines of Drosophila melanogaster. Expression of GAL4 in each line is controlled by a different, defined fragment of genomic DNA that serves as a transcriptional enhancer. We used confocal microscopy of dissected nervous systems to determine the expression patterns driven by each fragment in the adult brain and ventral nerve cord. We present image data on 6,650 lines. Using both manual and machine-assisted annotation, we describe the expression patterns in the most useful lines. We illustrate the utility of these data for identifying novel neuronal cell types, revealing brain asymmetry, and describing the nature and extent of neuronal shape stereotypy. The GAL4 lines allow expression of exogenous genes in distinct, small subsets of the adult nervous system. The set of DNA fragments, each driving a documented expression pattern, will facilitate the generation of additional constructs for manipulating neuronal function. synapse was substantially elevated, at the endocytic zone there was no enhanced polymerization activity. We conclude that actin subserves spatially diverse, independently regulated processes throughout spines. Perisynaptic actin forms a uniquely dynamic structure well suited for direct, active regulation of the synapse.

For the overall strategy and methods used to produce the GAL4 lines:

Pfeiffer, B.D., Jenett, A., Hammonds, A.S., Ngo, T.T., Misra, S., Murphy, C., Scully, A., Carlson, J.W., Wan, K.H., Laverty, T.R., Mungall, C., Svirskas, R., Kadonaga, J.T., Doe, C.Q., Eisen, M.B., Celniker, S.E., Rubin, G.M. (2008). Tools for neuroanatomy and neurogenetics in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 9715-9720. http://www.pnas.org/content/105/28/9715.full.pdf+html synapse was substantially elevated, at the endocytic zone there was no enhanced polymerization activity. We conclude that actin subserves spatially diverse, independently regulated processes throughout spines. Perisynaptic actin forms a uniquely dynamic structure well suited for direct, active regulation of the synapse.

For data on expression in the embryo:

Manning, L., Purice, M.D., Roberts, J., Pollard, J.L., Bennett, A.L., Kroll, J.R., Dyukareva, A.V., Doan, P.N., Lupton, J.R., Strader, M.E., Tanner, S., Bauer, D., Wilbur, A., Tran, K.D., Laverty, T.R., Pearson, J.C., Crews, S.T., Rubin, G.M., and Doe, C.Q. (2012) Annotated embryonic CNS expression patterns of 5000 GMR GAL4 lines: a resource for manipulating gene expression and analyzing cis-regulatory motifs. Cell Reports (2012) Doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.09.009 http://www.cell.com/cell-reports/fulltext/S2211-1247(12)00290-2 synapse was substantially elevated, at the endocytic zone there was no enhanced polymerization activity. We conclude that actin subserves spatially diverse, independently regulated processes throughout spines. Perisynaptic actin forms a uniquely dynamic structure well suited for direct, active regulation of the synapse.

For data on expression in imaginal discs:

Jory, A., Estella, C., Giorgianni, M.W., Slattery, M., Laverty, T.R., Rubin, G.M., and Mann, R.S. (2012) A survey of 6300 genomic fragments for cis-regulatory activity in the imaginal discs of Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Reports (2012) Doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.09.010 http://www.cell.com/cell-reports/fulltext/S2211-1247(12)00291-4 synapse was substantially elevated, at the endocytic zone there was no enhanced polymerization activity. We conclude that actin subserves spatially diverse, independently regulated processes throughout spines. Perisynaptic actin forms a uniquely dynamic structure well suited for direct, active regulation of the synapse.

For data on expression in the larval nervous system:

Li, H.-H., Kroll, J.R., Lennox, S., Ogundeyi, O., Jeter, J., Depasquale, G., and Truman, J.W. (2013) A GAL4 driver resource for developmental and behavioral studies on the larval CNS of Drosophila. Cell Reports (submitted).