Filter

Associated Lab

- Card Lab (3) Apply Card Lab filter

- Dickson Lab (5) Apply Dickson Lab filter

- Funke Lab (1) Apply Funke Lab filter

- Lavis Lab (2) Apply Lavis Lab filter

- Reiser Lab (1) Apply Reiser Lab filter

- Rubin Lab (1) Apply Rubin Lab filter

- Singer Lab (2) Apply Singer Lab filter

- Stern Lab (155) Apply Stern Lab filter

- Tillberg Lab (1) Apply Tillberg Lab filter

- Truman Lab (4) Apply Truman Lab filter

Associated Project Team

Publication Date

- 2025 (2) Apply 2025 filter

- 2024 (9) Apply 2024 filter

- 2023 (3) Apply 2023 filter

- 2022 (8) Apply 2022 filter

- 2021 (5) Apply 2021 filter

- 2020 (4) Apply 2020 filter

- 2019 (5) Apply 2019 filter

- 2018 (6) Apply 2018 filter

- 2017 (8) Apply 2017 filter

- 2016 (7) Apply 2016 filter

- 2015 (4) Apply 2015 filter

- 2014 (6) Apply 2014 filter

- 2013 (6) Apply 2013 filter

- 2012 (5) Apply 2012 filter

- 2011 (4) Apply 2011 filter

- 2010 (8) Apply 2010 filter

- 2009 (5) Apply 2009 filter

- 2008 (4) Apply 2008 filter

- 2007 (9) Apply 2007 filter

- 2006 (6) Apply 2006 filter

- 2005 (6) Apply 2005 filter

- 2004 (3) Apply 2004 filter

- 2003 (8) Apply 2003 filter

- 2001 (1) Apply 2001 filter

- 2000 (4) Apply 2000 filter

- 1999 (2) Apply 1999 filter

- 1998 (2) Apply 1998 filter

- 1997 (3) Apply 1997 filter

- 1996 (3) Apply 1996 filter

- 1995 (2) Apply 1995 filter

- 1994 (2) Apply 1994 filter

- 1993 (1) Apply 1993 filter

- 1991 (3) Apply 1991 filter

- 1990 (1) Apply 1990 filter

Type of Publication

155 Publications

Showing 131-140 of 155 resultsWe tested whether transcription activator-like effectors (TALEs) could mediate repression and activation of endogenous enhancers in the Drosophila genome. TALE repressors (TALERs) targeting each of the five even-skipped (eve) stripe enhancers generated repression specifically of the focal stripes. TALE activators (TALEAs) targeting the eve promoter or enhancers caused increased expression primarily in cells normally activated by the promoter or targeted enhancer, respectively. This effect supports the view that repression acts in a dominant fashion on transcriptional activators and that the activity state of an enhancer influences TALE binding or the ability of the VP16 domain to enhance transcription. In these assays, the Hairy repression domain did not exhibit previously described long-range transcriptional repression activity. The phenotypic effects of TALER and TALEA expression in larvae and adults are consistent with the observed modulations of eve expression. TALEs thus provide a novel tool for detection and functional modulation of transcriptional enhancers in their native genomic context.

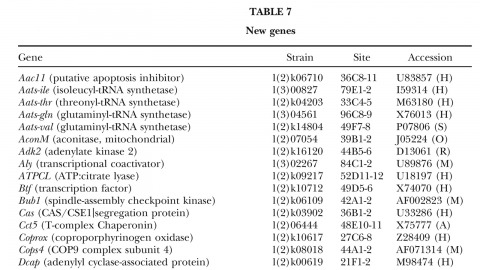

A fundamental goal of genetics and functional genomics is to identify and mutate every gene in model organisms such as Drosophila melanogaster. The Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project (BDGP) gene disruption project generates single P-element insertion strains that each mutate unique genomic open reading frames. Such strains strongly facilitate further genetic and molecular studies of the disrupted loci, but it has remained unclear if P elements can be used to mutate all Drosophila genes. We now report that the primary collection has grown to contain 1045 strains that disrupt more than 25% of the estimated 3600 Drosophila genes that are essential for adult viability. Of these P insertions, 67% have been verified by genetic tests to cause the associated recessive mutant phenotypes, and the validity of most of the remaining lines is predicted on statistical grounds. Sequences flanking >920 insertions have been determined to exactly position them in the genome and to identify 376 potentially affected transcripts from collections of EST sequences. Strains in the BDGP collection are available from the Bloomington Stock Center and have already assisted the research community in characterizing >250 Drosophila genes. The likely identity of 131 additional genes in the collection is reported here. Our results show that Drosophila genes have a wide range of sensitivity to inactivation by P elements, and provide a rationale for greatly expanding the BDGP primary collection based entirely on insertion site sequencing. We predict that this approach can bring >85% of all Drosophila open reading frames under experimental control.

The density and distribution of regulatory information in non-coding DNA of eukaryotic genomes is largely unknown. Evolutionary analyses have estimated that ∼60% of nucleotides in intergenic regions of the D. melanogaster genome is functionally relevant. This estimate is difficult to reconcile with the commonly accepted idea that enhancers are compact regulatory elements that generally encompass less than 1 kilobase of DNA. Here, we approached this issue through a functional dissection of the regulatory region of the gene shavenbaby (svb). Most of the ∼90 kilobases of this large regulatory region is highly conserved in the genus Drosophila, though characterized enhancers occupy a small fraction of this region. By analyzing the regulation of svb in different contexts of Drosophila development, we found that the regulatory architecture that drives svb expression in the abdominal pupal epidermis is organized in a dramatically different way than the information that drives svb expression in the embryonic epidermis. While in the embryonic epidermis svb is activated by compact and dispersed enhancers, svb expression in the pupal epidermis is driven by large regions with enhancer activity, which occupy a great portion of the svb cis-regulatory DNA. We observed that other developmental genes also display a dense distribution of putative regulatory elements in their regulatory regions. Furthermore, we found that a large percentage of conserved non-coding DNA of the Drosophila genome is contained within putative regulatory DNA. These results suggest that part of the evolutionary constraint on non-coding DNA of Drosophila is explained by the density of regulatory information.

Within all species of animals, the size of each organ bears a specific relationship to overall body size. These patterns of organ size relative to total body size are called static allometry and have enchanted biologists for centuries, yet the mechanisms generating these patterns have attracted little experimental study. We review recent and older work on holometabolous insect development that sheds light on these mechanisms. In insects, static allometry can be divided into at least two processes: (1) the autonomous specification of organ identity, perhaps including the approximate size of the organ, and (2) the determination of the final size of organs based on total body size. We present three models to explain the second process: (1) all organs autonomously absorb nutrients and grow at organ-specific rates, (2) a centralized system measures a close correlate of total body size and distributes this information to all organs, and (3) autonomous organ growth is combined with feedback between growing organs to modulate final sizes. We provide evidence supporting models 2 and 3 and also suggest that hormones are the messengers of size information. Advances in our understanding of the mechanisms of allometry will come through the integrated study of whole tissues using techniques from development, genetics, endocrinology and population biology.

What is the relationship between variation that segregates within natural populations and the differences that distinguish species? Many studies over the past century have demonstrated that most of the genetic variation within natural populations that contributes to quantitative traits causes relatively small phenotypic effects. In contrast, the genetic causes of quantitative differences between species are at least sometimes caused by few loci of relatively large effect. In addition, most of the results from evolutionary developmental biology are often discussed as though changes at just a few important 'molecular toolbox' genes provide the key clues to morphological evolution. On the face of it, these divergent results seem incompatible and call into question the neo-Darwinian view that differences between species emerge from precisely the same kinds of variants that segregate much of the time in natural populations. One prediction from the classical model is that many different genes can evolve to generate similar phenotypes. I discuss our studies that demonstrate that similar phenotypes have evolved in multiple lineages of Drosophila by evolution of the same gene, shavenbaby/ovo. This evidence for parallel evolution suggests that svb occupies a privileged position in the developmental network patterning larval trichomes that makes it a favourable target of evolutionary change.

A number of aphid species produce individuals, termed soldiers, that defend the colony by attacking predators. Soldiers have either reduced or zero direct reproductive fitness. Their behavior is therefore altruistic in the classical sense: an individual is behaving in a way that incurs reproductive costs on itself and confers reproductive benefits on another. However, comparison with the better–known eusocial insects (Hymenoptera, Isoptera) indicates that there are important differences between clonal and sexual social animals. Here we take a clone's–eye view and conclude that many facets of aphid sociality are best thought of in terms of resource allocation: for example, the choice between investment in defense and reproduction. This view considerably simplifies some aspects of the problem and highlights the qualitatively different nature of genetic heterogeneity in colonies of aphids and of other social insects. In sexually reproducing social insects, each individual usually has a different genome, which leads to genetic conflicts of interest between individuals. In social aphids, all members of a clone have identical genomes, barring new mutations, and there should be no disagreement among clonemates about investment decisions. Genetic heterogeneity within colonies can arise, but principally through clonal mixing, and this means that investment decisions will vary between different clones rather than among all individuals.

1. Defensive individuals, termed soldiers, have recently been discovered in aphids, Soldiers are typically early instar larvae, and in many species the soldiers are reproductively sterile and morphologically and behaviourally specialized. 2. Since aphids reproduce parthenogenetically, we might expect soldier production to be more widespread in aphids than it is. We suggest that a more useful way to think about these problems is to attempt to understand how a clone (rather than an individual) should invest in defence and reproduction. 3. Known soldiers are currently restricted to two families of aphids, the Pemphigidae and Hormaphididae, although they are distributed widely among genera within these families. We discuss the use of a phylogenetic perspective to aid comparative studies of soldier production and we demonstrate this approach using current estimates of phylogenetic affinities among aphids. We show that the distribution of soldier production requires a minimum of six to nine evolutionary origins plus at least one loss. 4. At least four main types of soldiers exist and we present and discuss this diversity of soldiers. 5. Most soldier-producing species produce soldiers within plant galls and we discuss the importance of galls for the evolution of soldiers. 6. We summarize the evidence on the interactions between soldiers and predators and between soldier-producing aphids and ants. 7. We present an optimality model for soldier investment strategies to help guide investigations of the ecological factors selecting for soldiers. 8. The proximate mechanisms of soldier production are currently very poorly understood and we suggest several avenues for further research.

Alterations in Hox gene expression patterns have been implicated in both large and small-scale morphological evolution. An improved understanding of these changes requires a detailed understanding of Hox gene cis-regulatory function and evolution. cis-regulatory evolution of the Hox gene Ultrabithorax (Ubx) has been shown to contribute to evolution of trichome patterns on the posterior second femur (T2p) of Drosophila species. As a step toward determining how this function of Ubx has evolved, we performed a series of experiments to clarify the role of Ubx in patterning femurs and to identify the cis-regulatory regions of Ubx that drive expression in T2p. We first performed clonal analysis to further define Ubx function in patterning bristle and trichome patterns in the legs. We found that low levels of Ubx expression are sufficient to repress an eighth bristle row on the posterior second and third femurs, whereas higher levels of expression are required to promote the development and migration of other bristles on the third femur and to repress trichomes. We then tested the hypothesis that the evolutionary difference in T2p trichome patterns due to Ubx was caused by a change in the global cis-regulation of Ubx expression. We found no evidence to support this view, suggesting that the evolved difference in Ubx function reflects evolution of a leg-specific enhancer. We then searched for the regulatory regions of the Ubx locus that drive expression in the second and third femur by assaying all existing regulatory mutations of the Ubx locus and new deficiencies in the large intron of Ubx that we generated by P-element-induced male recombination. We found that two enhancer regions previously known to regulate Ubx expression in the legs, abx and pbx, are required for Ubx expression in the third femur, but that they do not contribute to pupal expression of Ubx in the second femur. This analysis allowed us to rule out at least 100 kb of DNA in and around the Ubx locus as containing a T2p-specific enhancer. We then surveyed an additional approximately 30 kb using enhancer constructs. None of these enhancer constructs produced an expression pattern similar to Ubx expression in T2p. Thus, after surveying over 95% of the Ubx locus, we have not been able to localize a T2p-specific enhancer. While the enhancer could reside within the small regions we have not surveyed, it is also possible that the enhancer is structurally complex and/or acts only within its native genomic context.

The evolution of phenotypic similarities between species, known as convergence, illustrates that populations can respond predictably to ecological challenges. Convergence often results from similar genetic changes, which can emerge in two ways: the evolution of similar or identical mutations in independent lineages, which is termed parallel evolution; and the evolution in independent lineages of alleles that are shared among populations, which I call collateral genetic evolution. Evidence for parallel and collateral evolution has been found in many taxa, and an emerging hypothesis is that they result from the fact that mutations in some genetic targets minimize pleiotropic effects while simultaneously maximizing adaptation. If this proves correct, then the molecular changes underlying adaptation might be more predictable than has been appreciated previously.

The developmental mechanisms that regulate the relative size and shape of organs have remained obscure despite almost a century of interest in the problem and the fact that changes in relative size represent the dominant mode of evolutionary change. Here, I investigate how the Hox gene Ultrabithorax (Ubx) instructs the legs on the third thoracic segment of Drosophila melanogaster to develop with a different size and shape from the legs on the second thoracic segment. Through loss-of-function and gain-of-function experiments, I demonstrate that different segments of the leg, the femur and the first tarsal segment, and even different regions of the femur, regulate their size in response to Ubx expression through qualitatively different mechanisms. In some regions, Ubx acts autonomously to specify shape and size, whereas in other regions, Ubx influences size through nonautonomous mechanisms. Loss of Ubx autonomously reduces cell size in the T3 femur, but this reduction seems to be partially compensated by an increase in cell numbers, so that it is unclear what effect cell size and number directly have on femur size. Loss of Ubx has both autonomous and nonautonomous effects on cell number in different regions of the basitarsus, but again there is not a strong correlation between cell size or number and organ size. Total organ size appears to be regulated through mechanisms that operate at the level of the entire leg segment (femur or basitarsus) relatively independently of the behavior of individual subpopulations of cells within the segment.