How do large populations of neurons collaborate to implement the computations underlying flexible behavior? We use modern microscopy methods, computational approaches, and the study of behavior, genes and anatomy to investigate mechanisms underlying behavioral flexibility, memory, and learning. We study how both neurons and glial cells underlie these processes, which are relevant for species from fish to humans.

Lab Updates

Representative publications

A brainstem integrator for self-localization and positional homeostasis in zebrafish

Glia accumulate evidence that actions are futile and suppress unsuccessful behavior

Bright and photostable chemigenetic indicators for extended in vivo voltage imaging

Brainwide circuit interrogation at the cellular level guided by online analysis of neuronal function

Brainwide organization of neuronal activity and convergent sensory-motor transformations in larval zebrafish

The serotonergic system tracks the outcomes of actions to mediate short-term motor learning

Light-sheet functional imaging in fictively behaving zebrafish

Whole-brain functional imaging at cellular resolution using light-sheet microscopy

Brain-wide neuronal dynamics during motor adaptation in zebrafish

How do we observe the environment, decide which behavior to perform, and turn our experience into memories that determine our future behavior? These processes engage many brain areas, including sensory and motor areas, decision-related areas and neuromodulatory centers. We use modern microscopy methods to study activity across the entire brain of behaving zebrafish to map how large populations of neurons collaborate to implement the computations underlying behavior.

We study fundamental brain processes including motor learning, short-term memory and the generation of spontaneous behavior. We develop new experimental techniques to help answer biological questions, and design algorithms for analyzing the large datasets produced by our experiments. We like collaborating with other groups. Below are some examples of past and ongoing projects.

Glia-neuron interactions for behavioral states

Animals can shift between behavioral states, where they respond to sensory information and explore their environment in different ways. Some of these states arise because of accumulation of information about what happens when the animal performs certain actions. We study a behavior termed futility-induced passivity. When actions, like swimming, consistently fail to achieve their goals, like moving through the environment, animals tend to switch to a different behavior or even become passive for a period. In zebrafish this has been studied by placing animals in virtual arenas and switching from a closed-loop environment, where swimming leads to simulated displacement, to an open-loop environment, where swimming is futile and no longer affects the visual environment. By imaging from both neurons and a glial cell type termed radial astrocytes, it was found that noradrenergic neurons detect swim failures - i.e., swim bouts that do not lead to displacement. Such noradrenergic failure signals were integrated over periods of many seconds by radial astrocytes. Through glia-neuron interactions, the astrocytes then triggered a passive behavioral state that lasted many seconds, in part by the activation of nearby GABAergic neurons that suppress swimming. This work showed that astrocytes can play specific roles in neural computation, and can cause shifts in behavioral state. We published these findings recently in Mu et al., Cell, 2019.

Motor learning through neuromodulation

The serotonergic system mediates short-term motor learning by detecting the outcomes of swim actions and using those to modulate behavior. Kawashima et al., Cell, 2016

Mapping the brain for neural activity controlling exploratory locomotion

How does the brain control behavior when there is no guidance from the environment? Dunn et al., eLife, 2016

Left: path of a larval zebrafish spontaneously swimming in virtual reality. Middle: functionally identified neurons tuned to turning, overlaid with a map of spinal projection neurons. Right: activity of turning tuned neurons (green and magenta) and turning behavior (black).

Extended depth of field light-sheet microscopy

In collaboration with the Yuste lab we developed a system for random access light-sheet imaging: Quirin et al., Optics Letters, 2016.

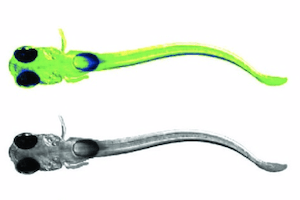

Whole-brain imaging and virtual reality

We developed a system for performing whole-brain, neuron-level recordings of the brains of larval zebrafish behaving in virtual reality: Vladimirov et al., Nature Methods, 2014.

Whole-brain activity without (left) and with (middle) sensory stimulation.

Large-scale data analysis

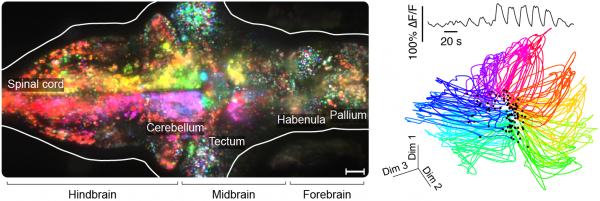

The Freeman lab collaborated with us to create a library for large-scale neural data analysis and apply it to whole-brain data: Freeman et al., Nature Methods, 2014. Resources, including analysis examples, links to code and example data, can be found here.

Left: orientation turning throughout the brain. Right: low-dimensional representation of whole-brain responses to directional visual stimuli.

Interested in joining the lab?

We have opportunities for postdoctoral researchers, PhD students (through the Johns Hopkins / Janelia graduate program, or graduate research fellowship program), and undergraduate students (through the Janelia summer undergraduate program).

For inquiries email ahrensm@janelia.hhmi.org.